At 3.30 on the afternoon of 21 January 1919 a group of twenty-seven men gathered in the Round Room of the Mansion House in Dublin. Just a month previously, each of them had been elected to the British parliament at Westminster. As candidates of the Sinn Féin party however, they had pledged not to take their seats if elected in protest at a delay in introducing Home Rule in Ireland and amid demands for an independent republic. The new MPs were meeting to establish their own independent parliament, Dáil Éireann, in complete defiance of British rule in Ireland.

Sinn Féin had won seventy-three of the 105 available Westminster parliament seats across the island of Ireland. The result represented an overwhelming rout of the Irish Parliamentary Party which for a generation or more had – under the leadership of Isaac Butt, Charles Stewart Parnell and later John Redmond – commanded majority support among the Irish nationalist electorate.

In about a quarter of constituencies, including all four in Kerry, Sinn Féin candidates were returned unopposed as Irish Parliamentary Party MPs stood aside in the face of anticipated defeat and a hugely successful campaign by Sinn Féin against the conscription of Irishmen to Britain’s world war effort and a clear and vociferous demand for Irish sovereignty.

Most of those elected were in prison at the time for offences against the realm and just twenty-seven members – each calling themselves Teachta Dála (TD) – of the new parliament assembled at the appointed time.

As those present were called to order, and following his appointment as Ceann Comhairle, Cathal Brugha read the roll of those returned at the 1918 election who now sat in a self-declared independent parliament. Brugha’s list included those representing the four parliamentary constituencies of Kerry:

| Co. Chiarraidhe (thoir) | Piaras Béaslaí | I láthair |

| Co. Chiarraidhe (thuaidh) | An Dr. S. Ó Cruadhlaoich | Fé ghlas ag Gallaibh |

| Co. Chiarraidhe (theas) | Fionán Ó Loingsigh | Fé ghlas ag Gallaibh |

| Co. Chiarraidhe (thiar) | Aibhistín de Staic | Fé ghlas ag Gallaibh |

The only Kerry representative i láthair or present was the new TD for East Kerry Piaras Béaslai.

His colleagues Dr James Crowley (North Kerry), Fionán Lynch (South Kerry) and Austin Stack (West Kerry) were each fé ghlas ag Gallaibh or ‘imprisoned by the foreigners.’ The Dáil asserted the exclusive right of the elected representatives of the Irish people to legislate for the country and adopted a Provisional Constitution and approved a Declaration of Independence. It also approved a Democratic Programme, based on the 1916 Proclamation of the Irish Republic, and read and adopted a Message to the Free Nations of the World.

Following the reading of a Declaration of Independence, the Ceann Comhairle, called on the East Kerry representative to speak the first words ever spoken by a Kerry deputy in Dáil Éireann:

PIARAS BÉASLAOI (ó OirthearChiarraighe): Is mór an onóir damhsa gur iarradh orm cur leis an ndearbhú ar Fhaisnéis Shaorstáit Éireann. Bhí sé d’amhantar agamsa is ag cuid agaibhse a bheith láithreach nuair do bunuigheadh an Saorstát Seachtmhain na Cásca, 1916, agus bhí laochraidhe cródha ann an uair sin- na daonie do rinn gníomh do réir a dtuairme. Ní mhairid na tréinfhir sin indiu: an namhaid do mhairbh iad. Acht na tréinfhir úd b’iad Fé ndear sgéal an lae indiu. Acht bíodh gur mór an truagh ná fuilid na laochraidhe sin in ár measc annso is deimhin dúinn go bhfuil spioraid gach n-aon aca annso in ár dteannta ar an nDáil seo, agus le congnamh Dé leanfaimíd an sompla d’fhágadar san in ar gcomhair. Deireann an Fhaisnéis go gcuirfam chum cinn an Saorstát ar gach slighe atá in ár gcumas. Cialluigheann san gníomh, agus ní bhfaighmíd staonadh ó éingníomhra, is cuma cad is deire dhóibh, príosún nó dortadh fola. Agus tá muinighin ag muinntir na hÉireann asainn-na, agus againn-na asta san. Déanfaidh Dáil Éireann gach éinnídh chum saoirse do bhaint amach agus chum an Fhaisnéis seo do chur chum críche.

Dáíl Éireann, 21 January 1919

The East Kerry deputy had been tasked with translating the Democratic Programme of the First Dáil – which had been drafted by the Labour Party leader, Thomas Johnson – into Irish, and read it into the record. Its opening words were:

We declare in the words of the Irish Republican Proclamation the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and to the unfettered control of Irish destinies to be indefeasible, and in the language of our first President, Pádraig Mac Phiarais, we declare that the Nation’s sovereignty extends not only to all men and women of the Nation, but to all its material possessions, the Nation’s soil and all its resources, all the wealth and all the wealth-producing processes within the Nation, and with him we reaffirm that all right to private property must be subordinated to the public right and welfare.

Dáil Éireann, 21 January 1919

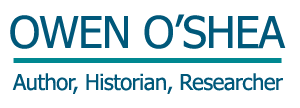

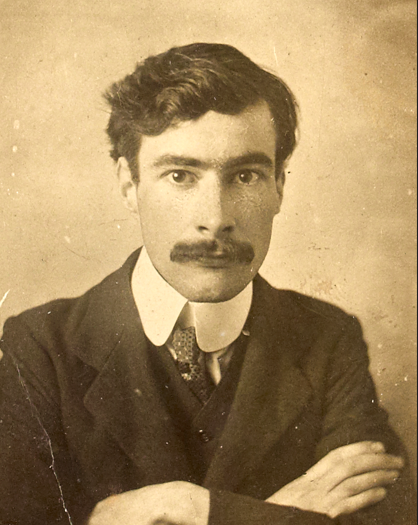

Beaslaí, having recited the Democratic Programme in Irish sat down and his colleague, Seán T Ó Ceallaigh, representing Dublin College Green – and later president of Ireland – read the document in English. A short time later, after less than two hours in session, the Dáil adjourned until the following day. So how did Piaras Béaslaí, a journalist who was born in Liverpool end up reciting such a significant statement of intent at the first sitting of Dáil Éireann? And who was he?

Liverpool was the birthplace of East Kerry’s first representative in an independent Irish parliament. Percy Frederick Beasley or Piaras Béaslaí as he was more widely known, was born in the city on 15 February 1881 to an Irish Catholic family. His father, Patrick Langford Beasley (or Beazley), was a journalist and a native of Curragh, Aghadoe near Killarney. Patrick was the editor of the Catholic Times newspaper in England. In his youth, Piaras holidayed with his uncle, Fr James Beazley in south Kerry.

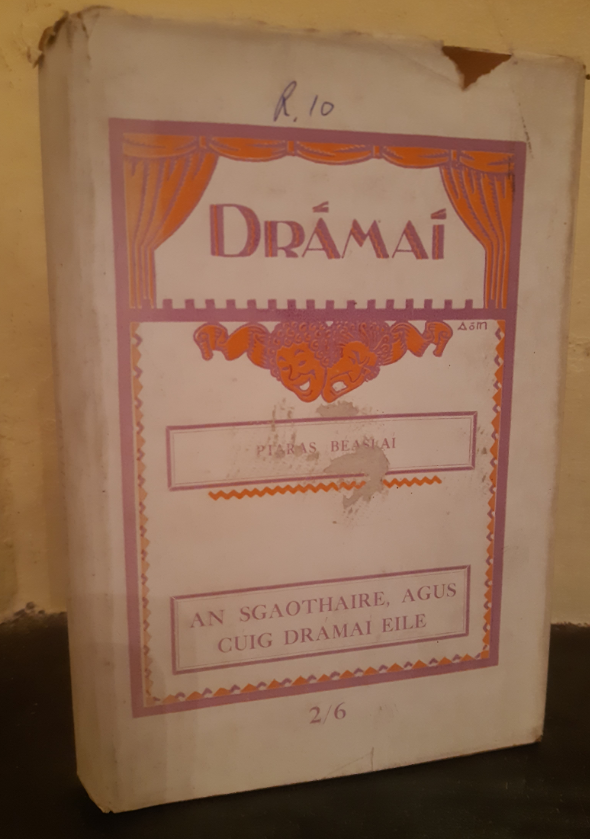

He was educated at St Xavier’s College in Liverpool and followed his father into journalism. The family moved to Dublin in 1906 and Piaras wrote for several publications including the Irish Independent and the Freeman’s Journal. A fluent Irish speaker, he had become active in the Gaelic League in Liverpool and joined the influential Keating Branch of the organisation in Dublin. He was involved in setting up the Irish language group, An Fáinne, in 1916 and became involved in staging Irish-language amateur drama at the annual Oireachtas, an Irish language festival, which, in 1914, was held in Killarney. Béaslaí began to write both original works and adaptations from foreign languages. One of these works, Eachtra Pheadair Schlemiel (1909), was translated from German into Irish.

Béaslaí soon became politically radicalised, joining the Irish Volunteers on their foundation in Dublin in November 1913 and he is credited with suggesting the name Óglaigh na h-Éireann for the organisation. Invited into the militant Irish Republican Brotherhood by Cathal Brugha, he became acquainted with Michael Collins as a member of its provisional committee. Prior to the Easter Rising, he took messages from Seán Mac Diarmada to Liverpool, from where they were transmitted to the leader of Clan na Gael in the United States, John Devoy. During Easter Week, Béaslaí was involved in the fighting in the north inner city including heavy engagements at Reilly’s Fort at the intersection of Church Street and North King Street under the command of Edward Daly.

He was jailed for his involvement in the rebellion in Portland and Lewes prisons in England. In June 1917, he was released on amnesty with hundreds of other prisoners. Returning to journalism, he became editor of An tÓglach, the Irish Volunteers magazine and began to write for the influential Volunteer publication An Claidheamh Soluis.

Béaslaí was chosen to contest the December 1918 general election for Sinn Féin in East Kerry where the Irish Parliamentary Party MP, Timothy O’Sullivan, was stepping down, like all of his party colleagues in Kerry. When the Returning Officer for South Kerry, David Roche, closed nominations on 4 December, Béaslaí was the only candidate put forward and Roche deemed him to be elected. His nomination papers were submitted by Killarney curate, Fr DJ Finucane who led a celebratory procession headed by two marching bands from the courthouse to the Market Cross in Killarney.[i] The new MP was not present for his nomination as he was reported to be ‘on the run’ though he later wrote that illness prevented him from being present. He did not appear in public until the first week of January at a ‘very large assemblage in the Killarney Sinn Féin Hall.’

Béaslaí was jailed in March and May 1919 for his associations with the republican newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis but was involved in a dramatic escape by six prisoners, including fellow TD, Austin Stack, from Strangeways Prison in Manchester in October. Scotland Yard described escapee Béaslaí as ’36, height 5ft 6ins., fresh complexioned, dark brown hair, proportionate build, oval face.’

Re-elected at the general election of 1921 for the newly formed seven-seat constituency of Kerry-Limerick West, he strongly supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty and delivered a lengthy speech in support of the agreement in the Dáil. He accepted the assertions of the Irish plenipotentiaries that the agreement, despite its flaws, offered a path to full independence. During the Dáil debate at the beginning of January 1922, he accused opponents of the Treaty of having no principles but rather, political formulas and of offering no realistic alternative:

What we are asked is, to choose between this Treaty on the one hand, and, on the other hand, bloodshed, political and social chaos and the frustration of all our hopes of national regeneration. The plain blunt man in the street, fighting man or civilian, sees that point more clearly than the formulists of Dáil Éireann. He sees in this Treaty the solid fact—our country cleared of the English armed forces, and the land in complete control of our own people to do what we like with. We can make our own Constitution, control our own finances, have our own schools and colleges, our own courts, our own flag, our own coinage and stamps, our own police, aye, and last but not least, our own army, not in flying columns, but in possession of the strong places of Ireland and the fortresses of Ireland, with artillery, aeroplanes and all the resources of modern warfare. Why, for what else have we been fighting but that? For what else has been the national struggle in all generations but for that?

Dáil Éireann, 3 January 1922

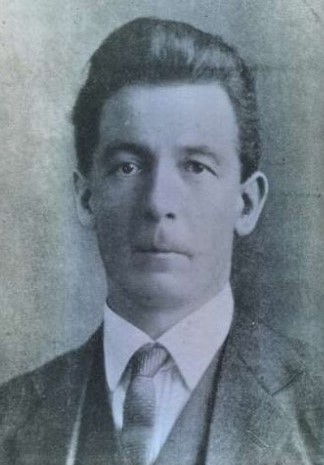

Béaslaí is credited with having coined the phrase ‘Irregulars’ to describe those opposed to the treaty. At the beginning of 1922, he travelled to the United States to raise support for the treaty and the provisional government. Though again returned to the Dáil in 1922 as a pro-Treaty candidate, he did not contest the 1923 election. He decided to leave politics to become a major general in the Free State Army and was Head of Press Censorship but he left the army in 1924 to focus on writing and journalism.

Outside of politics, Beaslaí was a prolific poet, playwright, novelist and author. Among his publications was the two-volume Michael Collins and the Making of a New Ireland which he began writing soon after Collins’ death in 1922. The Irish Independent said Béaslaí ‘loved Mick Collins as few men have loved another.’ He had introduced his cousin, Lily Mernin, to Collins and she became one of Collins’ top informants.

Béaslaí’s plays included Fear an Milliún Púnt, An Danar, and Bealtaine 1916. Béaslaí contributed columns to many national newspapers as well as The Kerryman in the 1950s. The extent of any political activity in later years was confined to lobbying for pensions for his former IRA comrades and he served as president of the Association of the Old Dublin Brigade.

National Archives files on Beaslaí suggest that he was mooted as a candidate for the presidency in 1945. The archives acquired his papers after his death and total some 17,000 different documents. He never married and died on 21 June 1965 and is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery in the same plot as fellow Kerry man Thomas Ashe and Peadar Kearney, who wrote The Soldier’s Song. The graveside oration was delivered by General Richard Mulcahy.

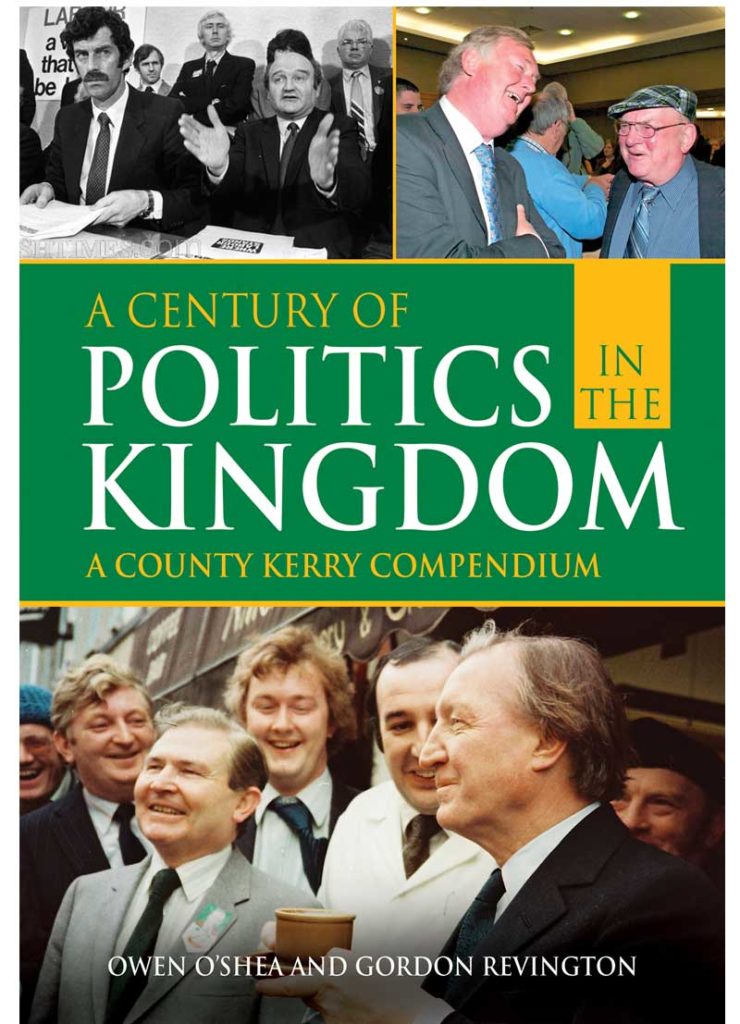

For more see: A Century of Politics in the Kingdom: A County Kerry Compendium – Irish Academic Press

[i] The Kerryman, 7 December 1918

[ii] The Kerryman, 9 February 1957

[iii] Kerry News, 8 January 1919

[iv] Kerry News, 13 January 1919

[v] The Kerryman, 1 November 1919

[vi] Dáil Debates, 3 January 1922.

[vii] Irish Independent, 30 June 1965