‘Why are all the people talking about Dick Spring, Mommy?’ a youngster asked her mother as they enjoyed lunch at a busy restaurant in the centre of Tralee. The chatter all around was dominated by politics. It was Wednesday, 18 February 1987 and a short distance away at the CYMS Hall at the end of Denny Street, the votes cast by the electors of Kerry North at the general election the previous day were being counted. ‘Because they are worried he might lose his job,’ the mother replied. ‘But,’ said the child, ‘can’t he get the dole, like Martin?’

How prophetic it was that just four days before the 1987 general election, The Kerryman lead headline read ‘Spring sounds the alarm.’ The report explained that Dick Spring, the Tánaiste, leader of the Labour Party, and TD for Kerry North was alleging there was a sophisticated campaign to undermine his position and cost him the Dáil seat he had held since 1981 – and which his father, Dan, had held without a break since 1943. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael were conspiring to split his vote, Spring told a press conference. Just weeks before, Spring had walked out of the coalition government which Labour had put together with Fine Gael under Garrett FitzGerald at the beginning of 1983. The coalition had struggled to balance the books in the midst of an economic recession and a dispute over health service cuts. Labour was in the doldrums and had been at five percent in one pre-election opinion poll. But despite the unpopularity of the government and the prevailing economic crisis, The Kerryman noted that anything less than Spring heading the poll in Kerry North would be ‘a sharp rebuke to the Kerryman who has had such a high profile in Irish politics in the past five years.’

A week later, when the ballot boxes were opened, Spring’s worst fears were almost realised. Like many candidates when the boxes are emptied, he didn’t go to the count first thing and instead waited at home for news from the tallymen. But when nobody had contacted him by 11am his suspicions grew. When his brother, Arthur, turned up, with ‘his chin down around his knees,’ on the doorstep at noon, he knew there was a problem – a quick calculation and Spring was convinced he would lost out by about twenty-five votes. Spring’s first preference return was down ten percent on the November 1982 poll and had collapsed by almost 3,000 votes to 6,739. In a spectacular performance, Fine Gael senator and former Kerry senior football captain, Jimmy Deenihan, had polled over 10,000 votes to surge to the head of the poll, ahead of Fianna Fáil’s Denis Foley on 7,611 and Fianna Fáil’s Tom McEllistrim on 6,161.

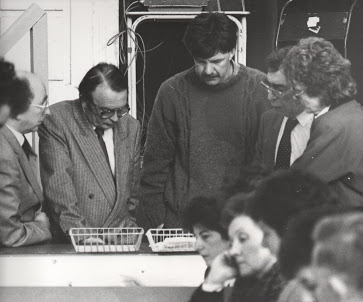

With Deenihan elected comfortably on the first count and Denis Foley taking the second seat thanks in part to a healthy transfer from the third Fianna Fáil man in the field, Dan Kiely, the Labour leader and Tom McEllistrim were left to the slog out for the last seat. At the end of the sixth and final count just after 10pm, McEllistrim was just five votes behind Spring and returning officer, Louise McDonagh declared that Deenihan, Foley and Spring had been elected. McDonagh later described what followed as ‘one of the most traumatic nights of my life.’ Tom McEllistrim, a former junior minister whose family had been represented in the Dáil since 1923, demanded a recount immediately and so began one of the most gripping electoral battles in the history of Irish politics.

In the only known case of the popular and well-known Ideal Homes Exhibition interfering with the timing of the counting of votes in an Irish general election, count staff were forced to commence the recount immediately rather than adjourn until the following day as the count centre was needed to host the interior decorating roadshow. McDonagh, whose father, Louis, from Listowel had been a county councillor for many years, had little choice but to proceed and the scrutiny of the ballots began all over again, not least because finding another secure location where the ballots boxes could be held overnight would have been difficult, as she later recalled:

With hindsight and the experience I now have, I would have postponed the recount until the next day. I would never again start a recount at twelve o’clock at night … (but) I would have had to remove everything to a different counting centre … I had the late Donie Browne (former state solicitor for Kerry) with me as my legal adviser … he was brilliant and knew proportional representation better than anybody I had ever known.

The Kerryman captured something of the drama as well as the fatigue as the clock ticked on into the wee hours and total of 34,000 papers were rechecked and scrutinised:

‘In the hall, or the streets and in the pubs, people referred to friends, brothers, mothers and sisters who could have “swung it” had they voted. Everyone seemed to know someone who was going to vote to Mac or Spring but didn’t. By midnight it became clear that the recount would go on until about 3.00am and each passing minute after that they seemed to draw more people to their beds … As the clock struck one a hard core of around 250 dedicated followers remained – determined to stick it out till the sweet or bitter end.’

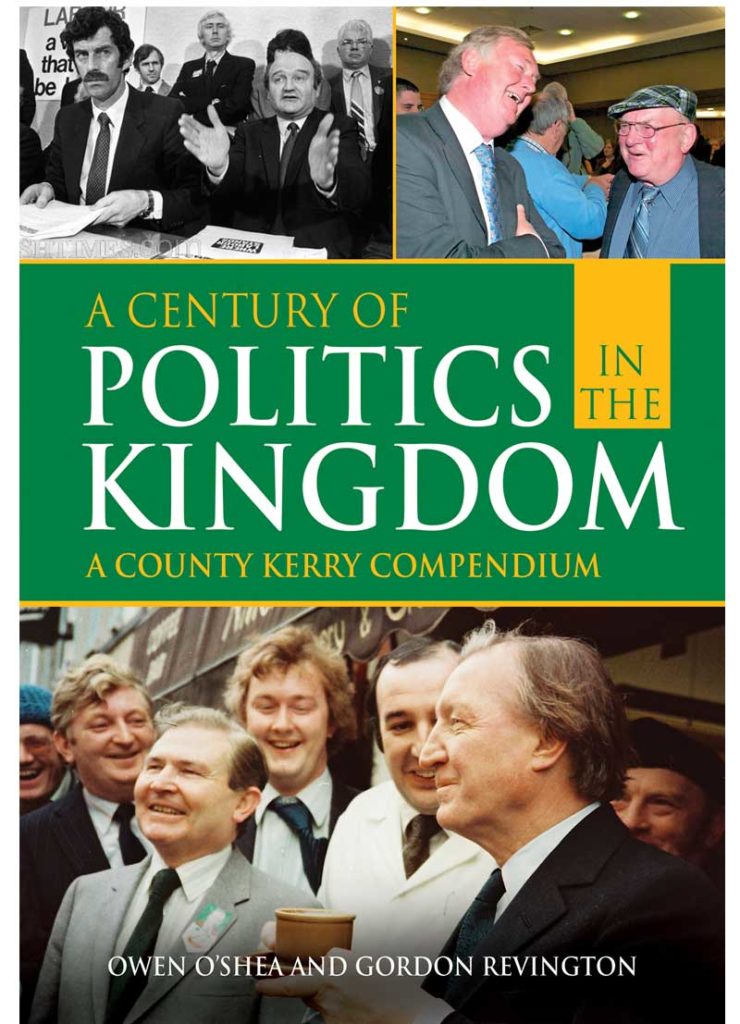

To read the full story, see ‘A Century of Politics in the Kingdom – A County Kerry Compendium’ by Owen O’Shea and Gordon Revington’ available from Merrion Press on A Century of Politics in the Kingdom: A County Kerry Compendium | Irish Academic Press