A vicious assault on two sisters in Kenmare a century ago, as the Civil War came to an end, prompted a major political crisis and led to one of the most shocking cover-ups of Free State army brutality in Kerry

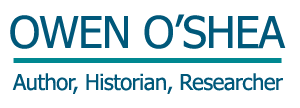

A few minutes before 1am on Saturday, 2 June 1923, the MacCarthy family of Kenmare were woken by loud knocking on the front door of their home, ‘Erinville.’ It was the home of the local doctor, Randall MacCarthy – a former member of the British army medical corps – and his family.

21-year-old Florence, or Flossie as she was better known, answered the door. Perhaps it was a local resident who needed the help of her father. As she opened the door, a masked man grabbed Flossie and dragged her out the front door.

Flossie’s 19-year-old sister, Jessie, was coming down the stairs when she too was dragged outside by the hair and pulled along the ground into the garden.

Flossie and Jessie were manhandled and stood upon. They were flogged with leather belts across the back, ‘with nothing to protect them but their pyjamas.’ Flossie stated that her sister was lying on the ground, ‘one man standing on her, the other beating her with the Sam Brown belt.’

The sisters were brutally beaten and were left ‘black and blue.’ One account alleged that they were sexually assaulted.

In the garden of ‘Erinville’, they had ‘dirty motor oil’ rubbed into their hair by three assailants. The application of oil or grease to women’s hair, which was very difficult to wash out, had been a feature of attacks on women during the War of Independence and the Civil War and was designed to degrade and humiliate victims.

Who instigated such a vicious assault on the two women and why?

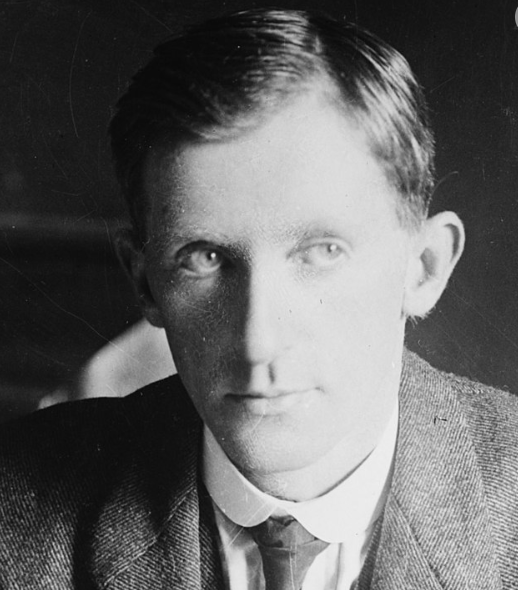

Early the following morning, army officers visited the scene and discovered a Colt revolver in the grounds of ‘Erinville’. It belonged to Major General Paddy O’Daly. O’Daly, the much-despised head of the Kerry Command of the Free State army, was associated with the worst incidents of the Civil War in the county, including the massacre at Ballyseedy in March 1923.

The other assailants were Captains Jim Clark and Edward Flood, who had prepared the bomb which was used to execute IRA prisoners at Ballyseedy.

But why had O’Daly, Clark and Flood beaten up the daughters of a highly-respected medical doctor and a known supporter of the Free State?

During the Civil War, Flossie and Jessie MacCarthy had socialised with two local soldiers Lt Michael Higgins and Capt Niall Harrington. The MacCarthys were invited to a dance organised by the Kerry Command but they declined the invitation, insisting: ‘We will not have anything to do with murderers.’

The remark – a reference to Free State army brutality in Kerry – seems to have infuriated O’Daly who forbade Higgins and Harrington from any contact with the MacCarthys, but the soldiers and the sisters continued to see each other. There were also suggestions that Dr MacCarthy had passed derogatory comments about the army locally.

Immediately, the army and the government moved to cover up the incident.

The Minister for Defence, Richard Mulcahy established a military court of enquiry which sat at O’Connor Barracks in Kenmare between 26 and 28 June. Seventeen witnesses gave evidence including Flossie and Jessie MacCarthy.

The investigation was a sham. It was alleged that one of the sentries on duty at the army barracks on the night of the assaults was denied the opportunity to testify that he had seen the three accused washing grease from their hands on their return from ‘Erinville.’ The Dáíl was later told that other persons who were to give evidence were ‘whisked away to distant parts of a country.’

The investigating officers found Flood guilty of assault but O’Daly and Clark were declared innocent. By this time, however, Captain Flood had fled Kenmare, with ‘scrape marks about his face.’

The incident prompted a full-scale political crisis at the highest levels of government. The Judge Advocate General, Cahir Davitt insisted that the matter could not be ‘hushed up’ and questioned why such ‘interference by force’ with ordinary citizens was being tolerated in the army in Kerry.

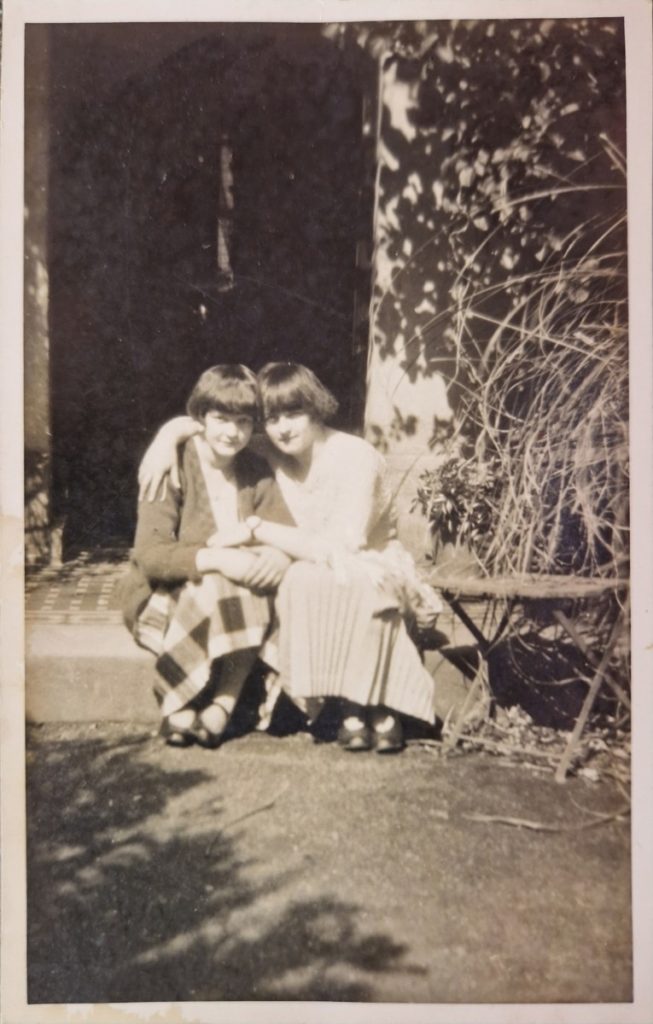

Mulcahy – who was also Commander in Chief of the army – resisted any attempt to convene an army court martial following the enquiry in Kenmare. He claimed O’Daly had denied to him that he had any involvement in the matter. In the same way as Mulcahy had stood by O’Daly after Ballyseedy, so too did he shamelessly again stand by the top man in his army in Kerry.

There was another minister who took a different attitude however. Kevin O’Higgins, the Minister for Justice, was disgusted by the attack on the MacCarthys and raised the matter with the head of government, WT Cosgrave. Furious about Mulcahy’s attitude, O’Higgins threatened to resign from government if the perpetrators were not brought to justice.

Meanwhile, the government asked the Attorney General, Hugh Kennedy, to write a report on the case. It was a report which was full of ‘misogyny, hypocrisy and arrogance’. Flossie and Jessie were dismissed as ‘not city people’ and ‘easy associates’ with soldiers. He also cast doubt on the extent of their injuries and concluded that accusations of a flogging were not ‘credible.’

Remarkably, the Attorney General insisted there was ‘not one shred or tittle of evidence’ against O’Daly and Clark and that evidence against Flood was ‘of the flimsiest character’ and contradictory.

The government accepted Kennedy’s deeply flawed findings. Kevin O’Higgins and Richard Mulcahy engaged in ‘bitter exchanges’ at the Cabinet table but the government finally agreed that if the MacCarthys wanted to pursue criminal charges, it would be a matter for themselves. The government could, and would, do no more.

One of those at the Cabinet table, the Minister for Finance, Ernest Blythe believed that ‘no great harm was done’ and ‘the outrage was more an indignity than anything else.’ It seemed to him that it was merely a case of ‘a couple of tarts getting a few lashes.’

Later that summer, Dr MacCarthy’s wife and daughters were at the cinema when two army officers, one of whom was drunk, came in and sat behind them. The intoxicated officer whispered to the MacCarthy sisters: ‘What oil do you use for your hair? Is it motor grease?’

The incident prompted the family to leave Kenmare for a break in England as Flossie and Jessie were ‘unable to sleep and were in constant dread of other attacks at night’ and who had endured ‘mental torture.’

For several years, the MacCarthy family continued their campaign for justice. In 1927, there was an angry exchange of letters between Dr MacCarthy, who was a supporter of Cumann na nGaedheal, and Kevin O’Higgins.

MacCarthy insisted again that justice had not been done. He had gone to Dublin with his daughters to be interviewed by the State Solicitor in 1923 and four years later still had related out of pocket expenses which had not been paid. He wrote to O’Higgins:

‘When I see your title [Minister for Justice] … I wonder what justice you meted out to me and mine. It is now over 3½ years since 3 prominent officers of the Free State Army brutally assaulted my daughters and up to this no compensation has been tendered by you …’

(National Archives)

The MacCarthys never received justice nor was any ever prosecuted for brutally attacking Flossie and Jessie in the dead of night.

100 years on, the so-called Kenmare Case remains one of the most outrageous examples of Free State army violence in Kerry. It also remains one of the most appalling political cover-ups in Irish history.

(Source material: Department of Justice Files, National Archives; No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry by Owen O’Shea)

For more see: No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry – Irish Academic Press