There is little dispute that Kerry was the location of the many of the worst excesses of the Irish Civil War and that it was more acrimonious, divisive and protracted than in most of the rest of the country. The events of March 1923, particularly those which occurred which occurred on 6 and 7 March, certainly contributed to that belief.

At Knocknagoshel on 6 March 1923, a party of eight Free State soldiers went to investigate a tip-off about an IRA arms dump. The tip-off was a ruse devised by the local IRA brigade to lure the enemy into a trap. At about 2am as they moved stones to investigate the location where arms were allegedly buried, a mine which had been planted by the IRA, exploded. Body parts were ‘strewn in all directions.’ Five soldiers including Paddy O’Connor (who was decapitated), Michael Galvin, Laurence O’Connor, Michael Dunne and Edward Stapleton died instantly and a sixth was so badly injured, his legs were amputated. The IRA members who set the mine were hiding in a dugout about a mile away. Sources suggest they heard the explosion and went back to sleep. The Knocknagoshel explosion represented the highest daily death toll among the Free State army in over six months.

Retaliation was as swift as it was ferocious. Over the following two weeks, nineteen Republican prisoners would die in Kerry at the hands of the Free State. Knocknagoshel prompted an army statement that any future barricades or obstructions on the roads would be removed by republican prisoners. ‘The tragedy of Knocknagoshel must not be repeated and serious disciplinary action will be taken against any officer who endangers the lives of his men in the removal of such barricades,’ was the clear order from Brigadier Paddy O’Daly. In his letter to officers in the Kerry Command he insisted that ‘the taking out of prisoners is not to be regarded as a reprisal, but as the only alternative left us to prevent the wholesale slaughter of our men.’ On the face of it, as Tom Doyle suggests in his book on the Civil War in Kerry, this warning was nothing more than that. However, its implementation was immediate and hugely repercussive.

On the night after the explosion and Knocknagoshel, and in a move which reverberated politically for generations, nine republican prisoners in Ballymullen Barracks in Tralee were taken to Ballyseedy on the Tralee to Killorglin road to clear a pile of rubble blocking the road. The nine, who had already been interrogated and abused in revenge for Knocknagoshel, were driven to the scene. It is suggested that one of the reasons they were selected from a wider group of prisoners was that they had no known links to the Catholic clergy or hierarchy so as not to antagonise the church which was actively and vocally supportive of the Free State and its leadership.

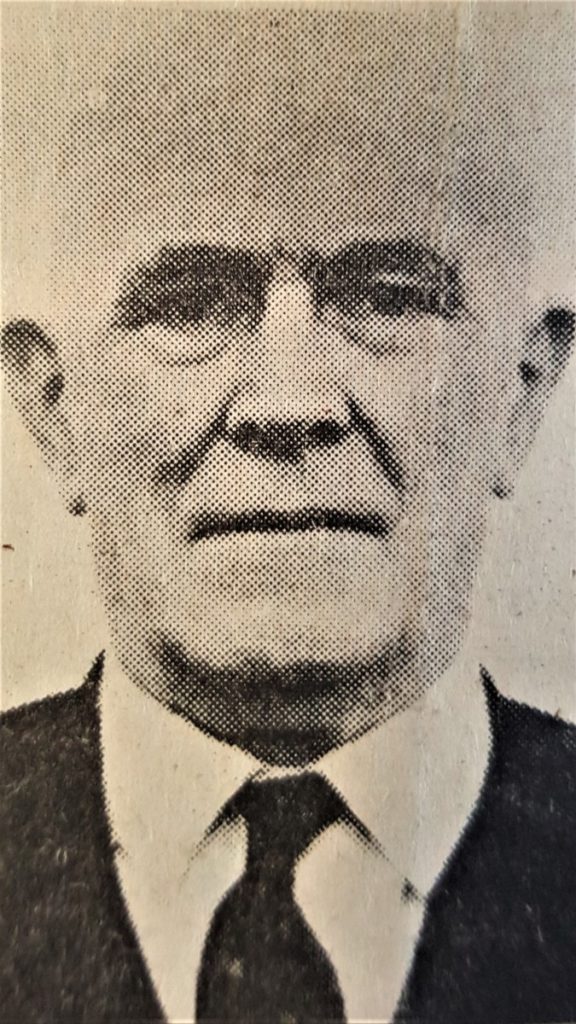

The army had planted a bomb in the rubble. They tied the prisoners by the wrists and their shoelaces and detonated the device. Eight of the nine were blown to pieces and killed instantly. The ninth, Stephen Fuller of Fahavane, Kilflynn, was thrown a considerable distance by the force of the explosion and, despite his injuries, managed to flee, taking him with him the only eyewitness account of the incident. Speaking in 1980, Fuller gave this account of what happened to a TV history of Ireland:

‘He gave us a cigarette and he said “That’s the last cigarette ye’ll ever again smoke.” He said “We’re going to blow ye up with a mine.” We were marched out and made to lie down flat in a lorry and taken out to Ballyseedy. The language was abusive language; it wasn’t too good. One fella called us Irish bastards and he was an Irishman himself. One of our lads asked to be left say his prayers. He said “No prayers, our fellas didn’t get any time for prayers” … They tied us then, our hands behind our back … and they tied us in a circle around the mine and they tied our legs then and our knees with a rope and they threw off our caps and said we could be praying away now as long as we like … “Goodbye lads” and up it went … and I went up with it …’

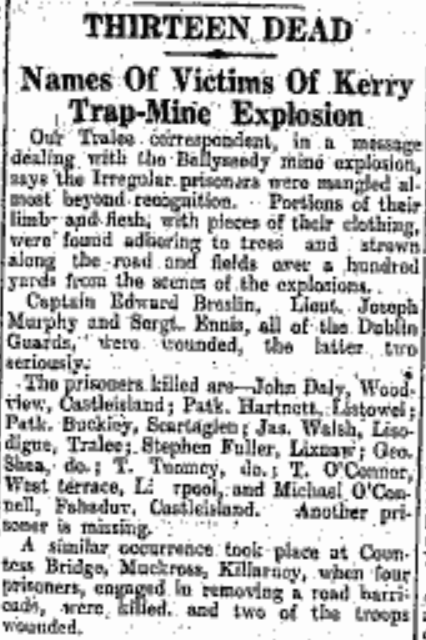

Such was the nature of the dismembering injuries sustained by Fuller’s comrades, republican writer Dorothy Macardle wrote that ‘the birds were eating the flesh off the trees at Ballyseedy Cross.’ The Cork Examiner reporter described how the prisoners were ‘mangled almost beyond recognition; portions of their limbs and flesh, with pieces of clothing, were found adhering to trees and strewn along the roads and fields over a hundred yards’ from the scene.

When the dismembered remains of the eight men who died were placed in coffins and returned to their families at Ballymullen Barracks, there followed a ‘frenzy.’ It is alleged that O’Daly ordered the army band to play ragtime music as the bodies were handed over to the families at the gates of the barracks. The families reacted furiously, throwing stones at the soldiers and smashing the army coffins on the ground as they placed the deceased in coffins they had brought themselves.

The funerals which followed prompted an outcry of condemnation of the actions of the Free State Army. As a result, it was decided that henceforth, prisoners who died in military custody in the Kerry Command areas would be buried by troops where they died rather than in their own parish. This was, as T Ryle Dwyer, argues, ‘tantamount to approving the barbarities that we being perpetrated and merely telling the soldiers to cover up their vile acts properly.’

Meanwhile, the police authorities moved quickly to absolve themselves of any connections with the deaths at Ballyseedy on the basis that it wasn’t reported to the Civic Guard in Kerry. The area was under curfew (11pm) at the time and no patrols were undertaken after this hour. ‘In any event,’ noted the superintendent Tralee, ‘in the Ballyseedy area at that time there were a considerable number of Irregulars, which rendered it unsafe for the Guards to patrol there.’

In the days and weeks after Knocknagoshel and Ballyseedy, the brutality of the conflict in Kerry continued on a downward spiral, seemingly out of control.

Stephen Fuller joined Fianna Fáil and won a seat for the party in Kerry North at the 1937 and 1938 general elections. It is claimed that he never mentioned Ballyseedy from an election platform. Stephen Fuller was also a county councillor between 1934 and 1938. He lost his Dáil seat in 1943 and retired from politics. He died in 1984. His son, Paudie Fuller was a member of Kerry County Council from 1972 to 1974 and 1980 to 1985.