If you were a passerby on the A-4212 regional road and were unaware of the significance of the site, the only thing that might draw your eye and rouse your curiosity is the Irish tricolour fluttering in the breeze alongside the Welsh standard on an adjacent flagpole.

If you decided to slow your car down and pull into the layby, the memorial stone on the roadside would offer a further clue about why the Irish flag was flying, somewhat incongruously, in this rural part of north Wales.

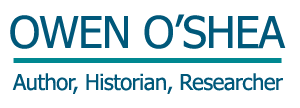

The name ‘Frongoch’, or to use the correct hyphenated Welsh name, ‘Fron-goch’ appears on one of the metal plaques on the large roadside boulder alongside an information panel which betrays the true historical importance of this location, particularly its significance in Irish history.

On 9 June 1916, a train pulled into the small train station at Fron-goch, a tiny village about five miles from the local town of Bala, and delivered the first of the Irish prisoners to the nearby prison camp. They were members of the Irish Volunteers who, to varying degrees, had taken part in the Easter Rising, a rebellion again British rule which had begun on Easter Monday and which had petered out after a week, with over 400 lives lost.

Fron-goch, which included a series of huts and buildings on the site of what was originally a whiskey distillery, had, until recently, been used to intern German prisoners of war. Now, two years into World War I, the British faced a new pressure on their prison network – the internees who had been arrested for their involvement in the Easter Rising. Initially held in a series of jails around England, Fron-goch was identified as a suitably remote, isolated and secure location to lock up the Irish rebels.

Among the prisoners were key figures in the Irish revolutionary period, including Richard Mulcahy, WT Cosgrave, Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins, all major political figures, as well as Volunteers from all over Ireland who had been party to the rebellion or preparations for revolt in their own counties.

The prisoners at Fron-goch – which was appropriately christened ‘Francach’, the Irish word for ‘rat’ such was the degree of rat infestation at the camp – numbered among them thirty-seven natives of County Kerry. Kerry had been central to the story of the Easter Rising, not least because of the attempt to land arms for the rebellion in Tralee Bay on Good Friday 1916 but also because it was where the first casualties of the Rising occurred when three Volunteers drowned at Ballykissane Pier near Killorglin.

The Kerry prisoners – see the full list of names below – including some of the principal leaders of republicanism in the county who either had, or would go on to have, a major influence on the course of Irish history. Each man had been arrested for actual or suspected involvement in the Rising, which had claimed the lives of four Kerry men in Dublin during Easter Week.

Among them were those who would become synonymous with the fight for Irish freedom in Kerry, including Billy Mullins, Michael Spillane, Paddy Cahill, Thomas O’Donoghue, Michael Knightly, Thomas McEllistrim and Denis Daly. Four of them – Cahill, O’Donoghue, McEllistrim and Daly – would go on to serve as Teachtaí Dála in an independent Irish parliament, Dáil Éireann.

The decision to place so many Irish Volunteers – eventually reaching some 1,800 in number – in the one cramped location and to allow them to mix freely in a relatively lax prison environment, would prove incredibly costly for the British government. Over the course of subsequent months, the Volunteers from all over Ireland, talked, sang, worked, learned, trained, shared and prepared for the next phase of the war to rid Ireland of the British control. The prison camp became known as the ‘University of Revolution’ as the internees learned about military tactics and organisation and plotted their next steps.

Apart from fine-tuning their approach to engagement with the Crown Forces in Ireland, the prisoners also found time to pursue their shared love for Irish culture and sport, not least through the playing of Gaelic football on a pitch adjacent to the prison huts. Before long, the pitch became known as ‘Croke Park’ as inter-county matches were hosted between rival teams.

One such tournament concluded with the holding of an ‘All-Ireland Final’ between Louth and Kerry (which Kerry won!) on 27 June 1916. (Perhaps Kerry should have 39 All-Irelands on the national roll of honour?!)

The presence among the prisoners of Dick Fitzgerald of Killarney, who had captained Kerry to back-to-back All-Ireland titles in 1913 and 1914 – and after whom Fitzgerald Stadium in Killarney is named – only added to the importance of Fron-goch as a temporary bastion of Gaelic football in the second half of 1916.

The vast majority of prisoners – no longer considered a serious threat – were released from Fron-goch on 23 December 1916 and many made it home, to a hero’s welcome, in time for Christmas.

Though they had only been there for six or seven months, the impact on the prisoners of their time in Fron-goch was profound. They had had time to lick their wounds after the Easter Rising, to re-group, to re-focus, to learn from each other, to re-charge their batteries, and, most importantly, to emerge with a renewed determination to pursue Irish freedom.

Today, sadly, none of the prison camp remains, and the local primary school occupies much of the site, which is in private ownership. But local man and former local councillor, Alwyn Jones, a history enthusiast with a passion for preserving the memory of the story of Fron-goch, lovingly maintains a small museum in the corner of a field adjacent to ‘Croke Park’.

It is testament to a corner of Wales which will be forever Ireland.

On 20 June 2024, the Mayor of Kerry, Jim Finucane, along with representatives from Kerry GAA and the Provincial Council of the GAA in Britain, unveiled a plaque in the museum which bears the names of the thirty-seven Kerry republicans who called Fron-goch their home for seven months in 1916. It was a fitting and moving occasion, one which I was deeply honoured to attend.

May the Kerry men of Fron-goch rest in peace.

Ar dheis Dé go raibh a h-anamnacha.

Bydded iddynt orffwys mewn heddwch.

37 Óglach ó Chiarraί

Eamon J Barry, Tralee

John Byrne, Ballymacelligott

Paddy Cahill, Tralee

Dermot Corkery, Dingle

Denis Daly, Cahersiveen

Michael Doyle, Tralee

Bill Farmer, Tralee

Dick Fitzgerald, Killarney

Thomas Fitzgerald, Dingle

Dan Healy, Tralee

PJ Hogan, Tralee

John J Horan, Tralee

William Horgan, Killarney

Michael T Knightly, Tralee

Thomas J McCarthy, Tralee

Tommy McEllistrim, Ballymacelligott

Joseph Melinn, Tralee

James Moriarty, Dingle

Michael Moriarty, Dingle

Billy Mullins, Tralee

Con Murphy, Rathmore

John O’Callaghan, Kenmare

Mortimer O’Connell, Cahersiveen

Michael J O’Connor, Tralee

Mortimer O’Connor, Abbeydorney

Thomas O’Connor, Ballymacelligott

Thomas O’Donoghue, Reenard

Dan O’Mahony, Castleisland

Jack O’Reilly, Tralee

John F O’Shea, Portmagee

Pat O’Shea, Killarney

Michael J O’Sullivan, Killarney

Timothy Ring, Valentia

Tom Slattery, Tralee

Michael Spillane, Killarney

Henry Spring, Firies

James Wall, Tralee

MORE: For biographical details on each of the Kerry prisoners see: Kerry 1916: Histories and Legacies of the Easter Rising – A Centenary Record – Owen O’Shea (owenoshea.ie)