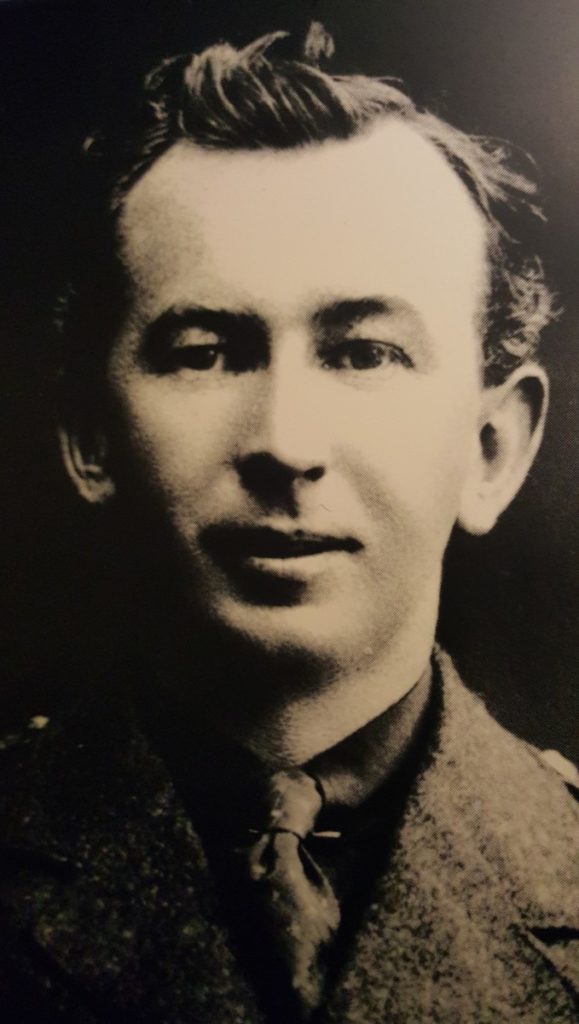

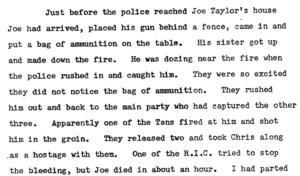

The plenipotentiaries who signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921 did not include any Kerry men or women. But three Kerry political figures did make their own contribution and were involved in the discussions that led to the Treaty, to varying degrees. Éamon de Valera invited Austin Stack to join him as part of the delegation which travelled to the first engagements with the British government on 12 July, shortly after the Truce which ended the War of Independence, came into effect.. On their arrival at Euston station in London, amid ‘intense fervour’ and shouts of ‘No Surrender’ from supporters, Stack was described in the Freeman’s Journal as looking ‘as active as when, years ago, he captained for the famous Kerry football team.’

Stack was not present for the talks themselves with De Valera briefing his colleagues as the talks progressed. On 20 July, the British proposals, which would ultimately form part of the discussions on a formal treaty, were received. Stack was disheartened and outraged: ‘I demurred at once,’ he wrote. Stack’s rejection of the proposals were a portent of what would become, for him, a campaign against any formula or agreement that would constitute anything less than a Republic and led him to ‘epitomise Republican opposition’ to what would be agreed in Downing Street in the early hours of 6 December 1921. Soon after, and ‘in a blazing mood,’ Stack voted against the pact at a meeting of the cabinet, which endorsed the Treaty by a margin of just a single vote. The seeds of division of subsequent of subsequent weeks and months were being sown.

Another Kerryman who played a role in these historic events was Fionán Lynch from Waterville. Lynch was a prominent figure in the Easter Rising and became close to Michael Collins and other senior leaders. Lynch had been elected MP for South Kerry in 1918 and was a member of the First Dáil, retaining his seat at the 1921 election. Lynch fought with the F Company of the Volunteers in and around the Four Courts during Easter Week and was jailed after the rebellion was crushed. He was on hunger strike in jail with fellow Kerryman Thomas Ashe in 1917 when he died following a forced feeding in Mountjoy.

In October 1921, Lynch, who maintained a lifelong friendship with De Valera, was invited to become part of the secretariat to the Irish delegation which went to London to negotiate with the British government. After its signing, he became one of its most vocal supporters and would go on to serve for ten years as a cabinet minister in the new Cumann na nGeadheal government after 1922.

The third Kerry man who featured in the Treaty negotiations was Michael Knightly from Ballyard, Tralee. A journalist, he was a housemate of Thomas Ashe in Dublin and took part in the Easter Rising at the GPO alongside The O’Rahilly from Ballylongford and fellow Tralee man, JJ McElligott. He spent time in jail in Frongoch after the Rising. Like Lynch, he was part of the secretarial team which travelled to London in the autumn of 1921 to hammer out a deal with Lloyd George. Knightly played no further role in politics, however, and he became editor-in-chief of the Dáil and Seanad debates.

As always, great, impartial information- Thank you Eoin

Owen, it’s great to get these snippets. While I would have a fairly good overall knowledge of the 1916-1923 years, all these smaller details are so interesting.