A dramatic and tragic four days in one Kerry village during Ireland’s Civil War

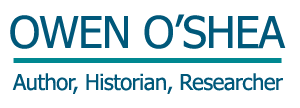

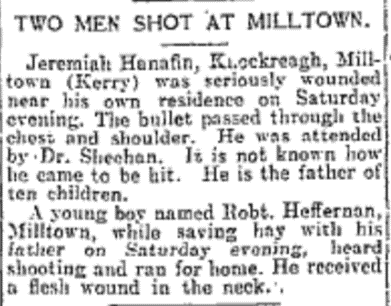

Jeremiah Hanifin had no known involvement in politics or any particularly strong views on the Treaty which divided the country and plunged Ireland into a bitter and bloody Civil War in 1922. And yet he became one of over a dozen innocent civilian victims of the war in County Kerry following a series of dramatic incidents and rising tensions in his native village in the autumn of 1922 which ultimately led to his shooting dead on the road outside his home.

Jeremiah Hanifin lived with his wife and ten children at Knockreigh, about one mile from the village of Milltown, on the Killarney road, in 1922. In the Census of 1911, Jeremiah is listed on the census form along with his wife, Julia and seven of those ten children, James, Mary, Julia, Catherine, Jeremiah, Nora and John. In 1922, Jeremiah Hanafin was aged 55 years. Hanifin was a farmer and worked the land near the mid-Kerry village like his father did before him.

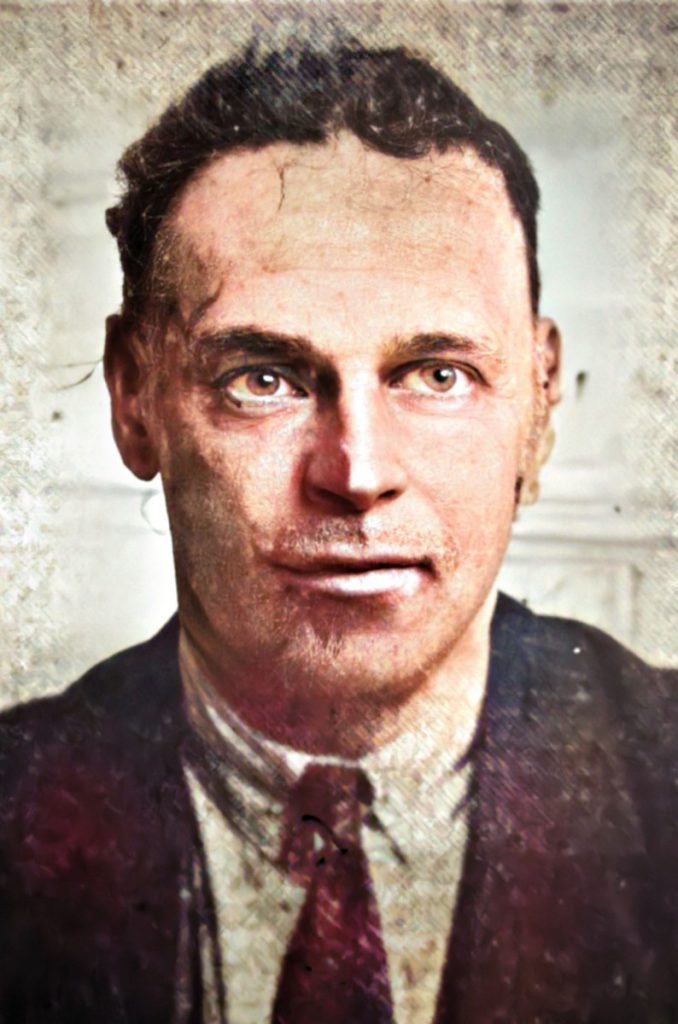

In the days before Jeremiah Hanifin died in September 1922, there was a lot of activity as well as heightened political tensions in Milltown and mid-Kerry generally. A few days before the tragedy, the anti-Treaty IRA looted a boat which had docked at the pier at Laghtacalla in Keel near Castlemaine. The boat, owned by the Spillers and Bakers milling company in England, was carrying a large quantity of flour. When it docked in Keel, the local IRA seized its cargo.

This sort of action by republicans was common at the time. The theft and looting of foodstuffs in transit had several objectives and consequences. Firstly, it deprived local businesses and residents of essential supplies. The IRA hoped that by causing this sort of disruption that they would turn people against the Free State government which was prosecuting the war against anti-Treaty republicans. Secondly, it prevented supplies from getting to Free State army barracks, like those in Castlemaine and Killorglin, in the hope that army forces would have to abandon rural barracks. And thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, goods and foodstuffs were stolen and then sold on for money which was then used to supply IRA men on the run and those hiding in rural dugouts. Apart from looting ships, boats and trains, the IRA also often resorted to stealing money, clothing and foodstuffs from shops and businesses. The net effect on the wider civilian population was enormous.

After the seizure of the very large quantity of flour in mid-September 1922, the local IRA stored the flour sacks at the former Watson’s creamery at Fybough in Keel and later at Rae’s Hotel in Boolteens. The hotel was run by William Emperor Rae and his wife, Ellen and had been a safe house for the IRA during the War of Independence. Their son Stephen Rae was a senior figure in the Keel IRA and had been sentenced to death for possession of a weapon towards the end of the conflict. He was only spared that fate because the war ended in July 1921.

But the IRA needed to put the flour to good use, and quickly. They decided to sell it to any local businesses they could find in return for money which could then be used to purchase food, clothing, boots and other supplies for the anti-Treaty IRA in the locality. Where better to find a home for hundreds of bags of flour than a local bakery. And so attention turned to Larkin’s Bakery in Milltown.

Larkin’s Bar and Public House was run at that time by Michael and Margaret Larkin. In the days after the seizure of the flour in Keel, the Larkins received a visit from the local IRA. The group was led by Jack Flynn. Flynn, a senior IRA figure from Brackhill, was among those who had fought at the Ballymacandy Ambush between Milltown and Castlemaine in June 1921. He had taken the anti-Treaty side at the beginning of 1922 and was now one of the leading republicans in the district.

Flynn and his comrades demanded that Michael and Margaret Larkin buy the flour which they could use in the bakery. The Larkins resisted, no doubt keen to avoid handling what were essentially stolen goods. But the Larkins came under significant pressure to comply. Flynn and the IRA forced Michael Larkin to buy 160 half sacks of flour and to part with £192 in return. Jack Flynn would later use the money to buy boots and clothing for his men.

The sale of the flour reached the ears of the Free State Army. Most likely acting on local intelligence, on Friday, 22September 1922, a large force of Free State soldiers arrived in Milltown. Many of them entered Larkin’s Bar and Bakery on Main Street. The soldiers were under the command of the notorious Commandant David Neligan, a senior figure in the Kerry Command of the army and a ruthless and violent associate of Major General Paddy O’Daly. Neligan was associated with some of the worst violence of the Civil War in Kerry including the massacres at Ballyseedy and Countess Bridge in March 1923.

The soldiers accused Michael and Margaret Larkin of having purchased flour from the local IRA, thereby handling stolen goods. Neligan and his men became aggressive and demanded that the Larkins hand over the flour into army custody. According to testimony given in court many years later, Neligan gave Michael Larkin ‘a few kicks.’ The soldiers became abusive and they took ten kilns of stout and broke them on the street, pouring the stout into the gutter. Bread and other baked goods from the bakery were destroyed and a bicycle was taken.

Michael Larkin was arrested and taken to the Free State army barracks at the Great Southern Hotel in Killarney, where he remained in custody until December 1922. In his diary, Major Leeson-Marshall of nearby Callinafercy House noted: ‘FS [Free State] men broke up his [Larkin’s] porter barrels & took away him & some tons of flour.’

The army took ownership of the dozens of sacks of flour from Larkin’s and decided to transport them to Killarney. In the absence of enough army vehicles, the soldiers commandeered horses, ponies, traps and carts from the village. One of those from whom such transport was commandeered was Michael Quirke from Farranamanagh, Milltown, a neighbour of Jeremiah Hanafin. Michael Quirke lived a short distance away from Hanafin’s on the Killarney road and he was an important figure in the locality. Quirke was described in his obituary as ‘one of the most progressive and popular figures in east Kerry’. He had been very involved in the Land War of the late nineteenth century and was the Secretary of the National League in Milltown. Michael Quirke was also active in the local Volunteers at the time of the Easter Rising and was said to ‘faced the Crown Forces and kept the flag flying in the most stormy and strenuous times in his district.’

On the day the Free State Army arrived in Milltown on 22 September 1922, Michael Quirke’s pony and trap were seized by the army. He also noticed other traps and lorries being used to take the flour from Larkin’s.

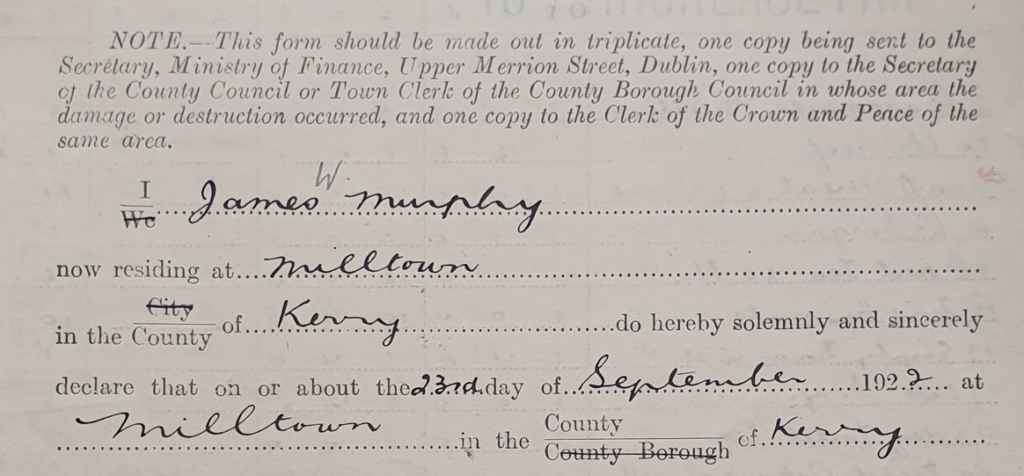

Meanwhile, one of Milltown’s best-known shopkeepers was going about his business. James W Murphy was on his way back from Tralee with a quantity of goods for his shop, which he ran with his father. When he arrived in Castlemaine, he was held up by the IRA who looted the goods he was carrying and Murphy arrived in Milltown with an empty cart. By the time he got back to Milltown, the Free State army were at Larkin’s and they commandeered Murphy’s horse and cart to help to transport the flour to Killarney. The soldiers forced James Murphy to drive his own cart to Killarney, laden down with sacks of flour.

On the following day, 23 September, the Free State army who remained in Milltown continued to transport the goods to Killarney, where the stolen flour has been taken. It is suggested locally that many of the soldiers were intoxicated, which was not an uncommon charge laid against army personnel at the time.

That afternoon, Jeremiah Hanifin was standing on the road in front of his house talking to a neighbour, Thomas Quirke. Thomas was a son of Michael Quirke, whose pony and trap had been seized the previous day. Jeremiah and Thomas were chatting as the Free State army convoy passed on its way from Milltown to Killarney.

Local lore holds that soldiers who had been drinking in Milltown spotted Hanifin and Quirke standing on the road and they challenged each other to target practice, wondering which of them could shoot the innocent bystanders. As an army vehicle travelled from Farran Cross towards Killarney, shots were fired indiscriminately.

An account given by Jeremiah’s wife, Julia Hanafin, describes what happened next:

A number of National Troops guarding a ‘convoy’ to Killarney came from the direction of Milltown and turned up a cross-road called Farran Cross. This cross is about 300 yards distant from where my husband was talking to Quirke. The main body of the troops had passed when a shot came from the direction of the Troops and wounded my husband in the stomach from the effects of which he died.

Jeremiah Hanafin was tended to by local medic, Dr Daniel Sheehan, but he had been mortally wounded. In his diary, Major Leeson-Marshall recorded the shooting of Hanifin, who he described as ‘a respectable farmer’ and who was killed ‘standing in the road.’

The shooting of Jeremiah Hanafin wasn’t the end of the violence in Milltown. According to the diary of Major Leeson-Marshall, a young man was injured when he was also shot on the same day near Kilderry Wood on the outskirts of the village. The IRA had cut trees and placed them across the road at Kilderry to prevent the movement of army troops. As they removed the trees, the soldiers engaged with the IRA. There was an exchange of gunfire and a local boy, 17 year-old Robert ‘Rabbie’ Heffernan, who was saving hay with his father at Parknacrush, was arrested. In a letter to his daughter, May, Major Leeson Marshall records that Heffernan was quizzed by soldiers about whether he had seen anything and he was marched down the hill into Milltown. During firing which followed, Heffernan sustained a bullet wound in the neck. He survived the injury.

Meanwhile, the local IRA was incensed that their illegal sale of flour to Larkin’s Bakery had been discovered by Commandant Neligan and his men. They were keen for revenge. Their attention turned to local shopkeeper, James Murphy, who had been one of those who had been coerced in transporting the flour to Killarney. According to files in the National Archives, Murphy was known to be a supporter of the Free State.

On the night of 23 September, just over twenty-four hours after the shooting of Jeremiah Hanifin near Farran Cross, the IRA broke into Murphy’s shop on Main Street in Milltown, looted almost everything there and loaded the goods onto carts in the street. A later claim for compensation detailed some £1,515 worth of damage to property and loss of property. Murphy was kidnapped by the IRA and held at an unknown location for a period of five weeks. The kidnapping of Murphy and the theft of all of the goods in his shop meant the shop was closed for several weeks. James Murphy was a father of eight young children at the time.

While all of this was unfolding in Milltown, another tragic incident claimed the life of a local Free State soldier in nearby Killorglin. John Looney, a farm labourer from Ballincarrig in Ballyhar had joined the Free State Army in August 1922. He was based at the Killorglin garrison at the Carnegie School on Market Street, which was one of the buildings held by the army in the town. On the night of 24 September at about 11pm, Private Looney was on duty in the guard room. His colleague, Private Stephen Stapleton accidentally discharged his rifle and Looney was shot in the abdomen. A doctor tried to save his life but Private Looney died two hours later. He had only been a soldier for about one month. Stapleton was exonerated and the incident was declared an accident.

As Private Looney’s grave was being dug at Dromavalla graveyard in Killorglin, the army posted sentries to protect the grave diggers and an exchange of shots, presumably between Free State and IRA forces, were heard as far away as Callinafercy. It is likely that Free State soldiers were in heightened state of agitation after the accidental shooting of their colleague.

Two days after the shooting of Jeremiah Hanafin and a day after James Murphy was kidnapped, the Free State army was back in Milltown in large numbers. According to testimony given many years later in court, Margaret Larkin stated that soldiers again entered her bar on Monday, 25September. The troops demanded drink and consumed a barrel of stout between them. They took all of the cigarettes from the bar as well as barm bracks from the bakery next door. Captains Wilson and Lyons were said to have stolen sugar, bread and butter from the premises. The troops became increasingly aggressive and one eyewitness, James O’Connor, described how one soldier fired a shot over Mrs Larkin’s head.

Jeremiah Hanafin was laid to rest in the cemetery at the White Church near Milltown on Wednesday, 27 September 1922, just as the Battle for Killorglin, a major engagement which resulted in five casualties, was reaching its climax.

The looting of a cargo of flour just a few days before had triggered a series of events which left a woman without her husband and ten young children without a father.

Jeremiah Hanafin was one of the forgotten victims of the Civil War in Ireland until a plaque was recently unveiled in his native Milltown to honour his memory and that of two other civilians from Milltown who were killed in unfortunate circumstances during some of Ireland’s darkest days.

The author is extremely grateful to the Hanafin family for providing images and information about Jeremiah Hanafin and to Liam O’Sullivan and Dr John Knightly for greatly assisting in researching this important story.