“Wait for a dead man’s shoes and you’ll end up barefoot,” warns an old English adage about the importance of taking action. At the removal of four police officers killed in a Co Kerry IRA ambush 100 years ago this month, however, schoolboy Thomas ‘Totty’ O’Sullivan saw no need to wait. Walking behind the bodies as they were transported on carts, he decided that a pair of their fine leather boots would make a valuable memento.

Sadly, Totty later recalled, his attempted theft was foiled by “a clatter from an old woman in a shawl who had joined the informal cortege . . . ‘Don’t you be robbin’ and shtaylin’ off the dead,’ she cried”.

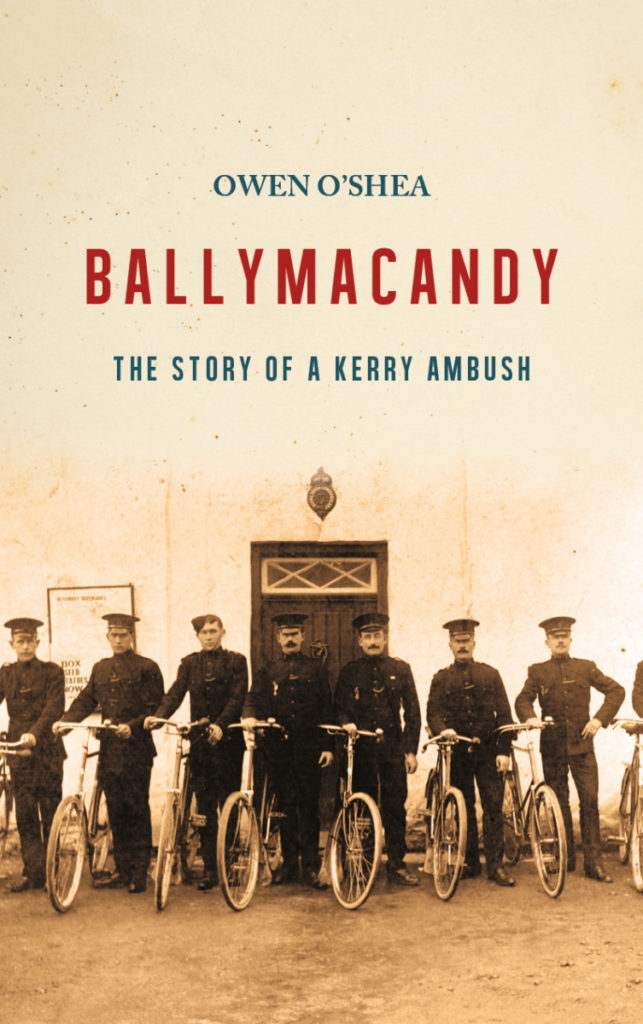

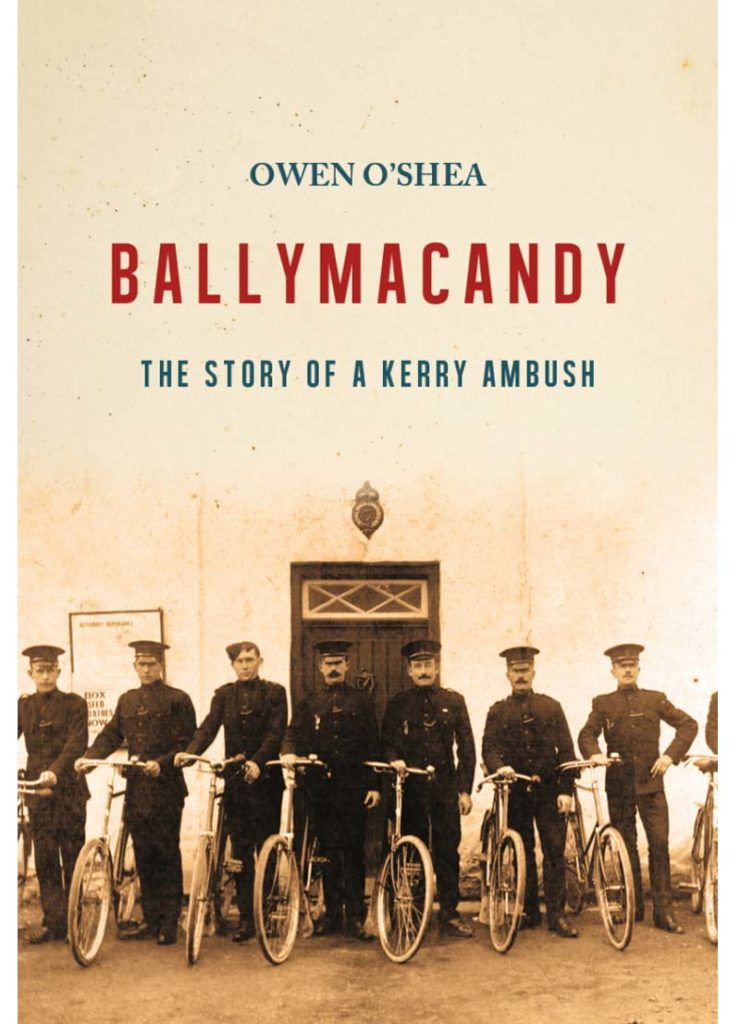

Colourful details such as these help to lift Owen O’Shea’s reconstruction of the Ballymacandy gunfight well above your average local history. Researching this exceptionally bloody incident from the War of Independence has been a labour of love for him, since its location between Milltown and Castlemaine is just a few fields away from where he grew up. By his own admission, however, securing oral testimony from the eye-witnesses’ descendants was no easy task.

“Boxes of medals were produced from cupboards, pictures taken down from mantelpieces, handwritten letters retrieved from shoeboxes,” O’Shea writes. “But there was also a constant and enduring refrain: ‘They didn’t really talk about what happened.’”

One man who did shed some light on the affair was IRA leader Dan Mulvihill. As O’Shea points out, his background “belies any romantic notion that those who fought the Black and Tans followed a universal personal and career trajectory”.

Mulvihill spent two years working in London, travelled the world as a steamship radio operator and almost joined the Royal Air Force. Fate intervened when his brother contracted tuberculosis and Dan was summoned home to run the family farm. He had a romantic attachment to the Kerry countryside and clearly loved the life of a flying column outlaw, later recalling wistfully, “It was grand to be young and on the run in Glencar.”

O’Shea also gives full weight to Mulvihill’s victims such as Sergeant James Collery, shrewdly noting how much they had in common. Collery was an absolutely typical Royal Irish Constabulary recruit in 1899: rural (from Co Sligo), Catholic, unmarried and the youngest son of a farming family. By 1921 he had fathered nine children and was personally popular in Milltown, but also found himself on the wrong side of history.

“[The average RIC man] now has no friends and young women shun him,” thundered a Kerry newspaper editorial. “He walks abroad with the expectation of instant death.”

An ambush on a lonely road might sound straightforward, but O’Shea’s detailed narrative shows what a complex military operation it was. Over 40 IRA volunteers were involved in attacking a cycling unit of 12 RIC officers and Black and Tans, starting a shootout that lasted between 30 and 45 minutes. When Totty O’Sullivan and his classmate Denis Sugrue arrived a few minutes later, they witnessed scenes that would stay with them forever.

“For us young lads it was an eerie atmosphere with the odour of gunpowder polluting the air . . . the only sign of life was the long figure of a woman crooning over the strewn bodies.”

O’Shea does a fine job of uncovering the story’s lesser-known tangents, including a traumatised IRA gunman who died by suicide shortly afterwards and a doctor whose failure to save one victim (five eventually died) was blamed on his republican sympathies. He also emphasises the role played by Cumann na mBan women who stored weapons, carried out intelligence work and provided first-aid treatment.

Meticulously researched and soberly written, the book ends with an anecdote that suggests time does not necessarily heal all wounds. In the late 1960s, an ex-Black and Tan who had escaped injury at Ballymacandy took a holiday near there and revealed his identity to a local publican. He was urged to visit Dan Mulvihill, on the grounds that “bygones were bygones, and sure wouldn’t it be a way to bury the hatchet?”

Mulvihill was not at home, however, which may have been just as well given his reaction when told about the tourist a few days later: “I’d have shot the bastard.”

Ballymacandy: Fascinating history of a Kerry ambush and what went unspoken | Business Post