Despite much activity in County Kerry during the week-long Easter Rising in 1916, there was just one discharge of a weapon in the county during the entire rebellion. The confused situation and the absence of instructions from headquarters as the GPO came under assault in Dublin, did nothing however to quell the undercurrent of republicanism and latent violence in Kerry as the Rising played out on the streets of Dublin and other parts of the country.

James (Jim) Riordan, a members of the Firies Company of the Irish Volunteers went into Firies village to buy a newspaper on the morning on Saturday, 29 April, less than a week after the Rising had erupted in Dublin and at the same time as its besieged leaders were contemplating surrender in a house on Moore Street. At the age of 16, Jim joined the Irish Volunteers in 1914 and soon rose to the rank of Lieutenant of the Firies Company. His brother, Patrick (Paddy) was also a member.

By the beginning of 1916, the Firies company was actively drilling and arming itself and boasted a membership of 75 men. Soon after midnight on Easter Monday, 24 April, the company assembled at the church in the village and marched to nearby Currans to join the company there. They marched onto Castleisland as the designated meeting point for companies in the Castleisland battalion where battalion officer, Dan O’Mahony was in command. Amid confusion and the lack of receipt of any further instructions, the local companies decided

… to disband temporarily, to meet every night during the week in their respective areas, all Volunteers to hold themselves in readiness for immediate mobilisation, one Volunteer to be appointed on full-time duty by each company to receive and deliver urgent communications when required, and, lastly, each Company Captain had to pledge himself that no untoward incident as regards attacks on armed enemy forces would be permitted.

The final element of that decision was to be sorely tested in Firies a few days later. Jim Riordan volunteered to act as the member on duty during the remainder of Easter Week. He oversaw the assemblies each night and awaited as the train arrived each morning at Molahiffe railway station in anticipation of a dispatch or orders from Dublin. An account published many years later claims that Jim, in full volunteer uniform, visited the railway station on the morning of Saturday, 29 April where local RIC members taunted him, saying ‘We’ll strip that uniform off you before the night, Riordan,’ to which he replied ‘I would like to see you try it.’

According to his brother, Paddy, Jim walked from his home at Longfield at 11 o’clock that morning to purchase a newspaper to see if there were any information about what was taking place in Dublin. He met two other local men named Costelloe and Donoghue. The three saw two RIC officers, Michael Cleary and Thomas McLoughlin who were based at Farranfore – dismount from bicycles before putting up a notice in the window of the post office announcing the introduction of martial law the outbreak of rebellion in Dublin.

Paddy noted that Costelloe or Donoghue made a remark within earshot the of the RIC men about Jim Riordan giving up his arms to which the officers replied ‘These damned Shinners should give up their arms.’ One account says that Jim went over to read the notice and ripped it down in full view of the constables.

As Riordan tried to pass Cleary and McLoughlin, one of the constables made to open his holster and the other started to unsling his carbine. Jim Riordan produced his Webley gun and fired at the policemen, wounding them both. The Irish Independent records that Cleary was shot in the left thigh and McLoughlin in the left arm. The wounded men were treated in O’Sullivan’s public house before being moved to the county infirmary.

From his home at Longfield, Paddy Riordan had heard the shots and recognised the sound of his brother’s gun. Jim ran home and was urged by Paddy and his father to flee to the home of a local Fenian, Tadhg Quirke. Within hours

… two carloads of RIC arrived at Longfield and they approached our house in single file. An RIC man named Kelly was in the lead, but when he came to the gate he funked going in and the rest of the RIC gathered up behind him. They then rushed the house; it was a thatched house by the side of the road. They started to wreck the place when they found we were not there. They smashed a fiddle, struck my father, broke windows and, entering an outhouse where milk was held for churning, they spilled the pans of milk and a barrel of cream on to the floor.

During the raid on the family home, a list of local Volunteers who held weapons was discovered and this prompted a number of arrests in the district and the arrival of several additional troops in Firies the following day.

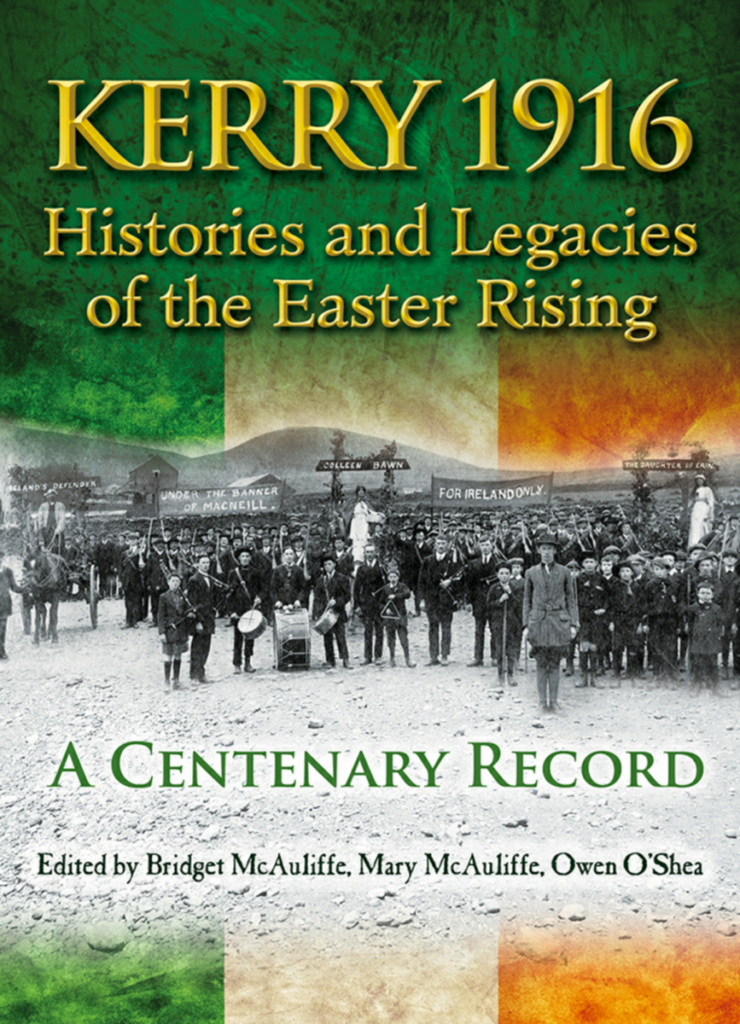

An extract from ‘Kerry 1916: Histories and Legacies of the Easter Rising – A Centenary Record’ available to buy at:

Book Kerry 1916 Histories and Legacies of the Easter Rising (kerry1916book.com)