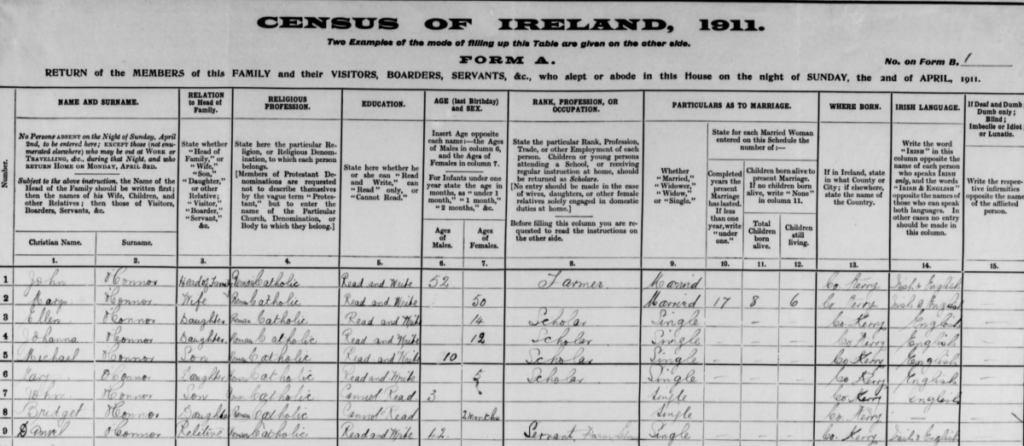

Twenty-two-year-old Johanna (Hannah) O’Connor had not a care in the world and was in ‘the midst of gaiety’ as she made her way home from a dance in Glenbeigh on the evening of Sunday, 2 September 1923. Hannah lived with her parents John and Mary at Keel, Glencar, deep in the valleys around the MacGillycuddy’s Reeks, along with two brothers and three sisters. Her brother, Michael, was a member of the Civic Guards, which later became An Garda Síochána.

The farmer’s daughter had earlier walked from her home for a distance of ‘four or five miles’, to enjoy music and dancing with her friend and cousins, Nancy Clifford and Katie O’Connor. The Civil War had been over for several months and social occasions such as dances and other gatherings had been taking place with increased frequency as largely peaceful times prevailed.

The dance that night in the Glenbeigh Hall attracted ‘a big crowd’ include ‘a lot of soldiers.’ After spending about an hour and a half at the dance, Hannah left with Nancy and Katie. They were in the company of a young soldier, Sergeant Jim Shea, who was off duty for the night.

When the group encountered a group of Free State Army soldiers a short distance from the dancehall, they engaged in conversation with them. Subsequent accounts suggest that the atmosphere was friendly: they were ‘all joking’. One of the trio remarked to Sgt. Shea that he had a lot of girls with him, to which Shea replied, ‘They are all Free State girls.’ Hannah O’Connor replied, ‘No, I’m a Die-Hard … Have a heart; love a Die-Hard.’

The remark, whether in seriousness or in jest, was perceived as being a reference to republicanism or hostility to the Free State. Whatever the intent of the remark, it had immediate consequences for Hannah.

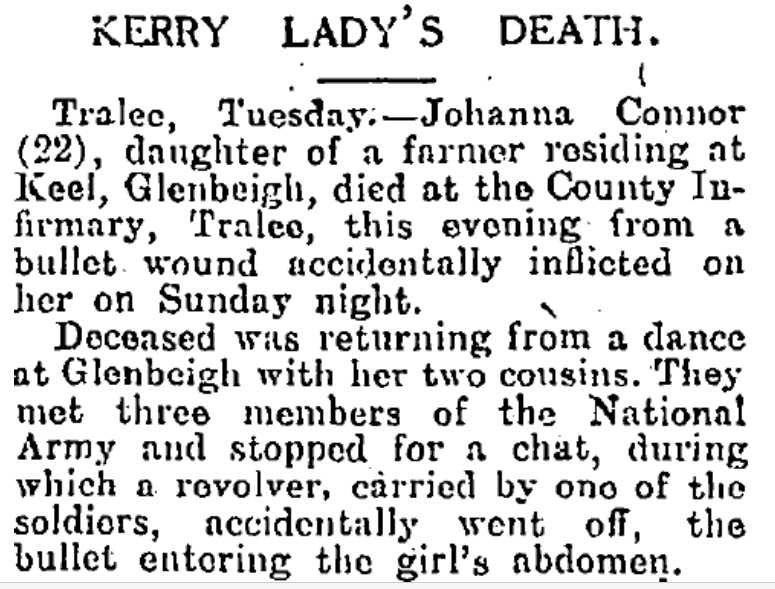

One of the soldiers, Lieutenant John Hunter, a member of the Armoured Car Corps with the Kerry Command of the army, drew his revolver and a shot was discharged. O’Connor was shot in the abdomen and collapsed into the arms of her friends. After being treated by the local doctor in Killorglin, Hannah was taken to hospital. Her condition deteriorated rapidly and she died the following day at the County Infirmary in Tralee.

On 5 September, the Cork Examiner reported on a ‘Kerry Lady’s Death’:

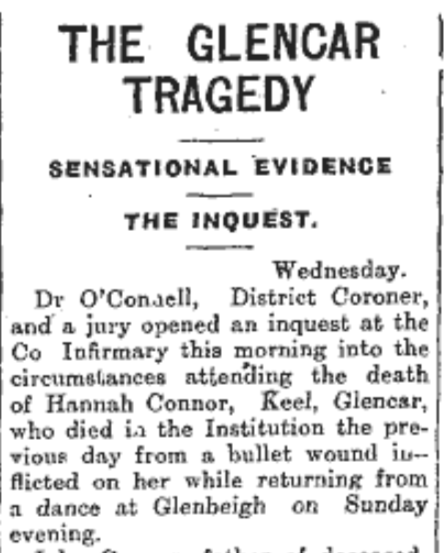

The inquest into Hannah O’Connor’s death opened on 6 September at the County Infirmary in Tralee under the District Coroner, Dr. O’Connell. Hannah’s father, John, gave evidence of identifying her remains. He had managed to speak to Hannah as she was dying and she recounted how she saw Hunter taking out his revolver before she was shot.

Katie O’Connor, Hannah’s cousin, told the inquest that they had left the dance some time between 9 o’clock and 10 o’clock along with Sgt Jim Shea. They met a group of soldiers about 50 yards outside Glenbeigh. After the exchanges between Hannah and the soldiers, Katie heard a shot. Along with her friends, Katie and Nancy, the soldiers managed to get the injured women into Guerin’s house nearby.

The moment they got into the light of the kitchen in Guerin’s [Katie said], they saw a hole in Hannah’s coat and knew that she was shot. After sitting in a chair in the kitchen for some time, her condition was getting worse so they took her upstairs, laid her on a bed and loosened her clothing. They saw the blood and found the wound. She asked to be taken to the doctor.

Lt Hunter, Hannah’s assailant, entered the house and asked ‘Is it [the bullet} gone through the back?’ to which Katie O’Connor replied ‘No.’ Hunter seemed upset and apologetic.

Local man Pat Griffin arrived in his motorcar and Hannah was taken to Dr Dodd in Killorglin. The soldiers, including Lt Hunter travelled with the injured woman in the car. Dr Dodd dressed the wound and recommended that Hannah be taken to hospital in Tralee. However, because of the lateness of the hour, he instead suggested she be kept in bed overnight and taken to hospital the following morning. Hannah was taken to the home of her aunt, Mrs Hartnett on Langford Street in Killorglin and was kept there overnight.

Katie O’Connor described a discussion she had at Hartnett’s with Lt Hunter. He admitted that he had fired the shot: ‘I thought there wasn’t a cartridge in the revolver,’ he said.

Before she had died, Hannah O’Connor had dictated a statement to the Civic Guards. It was read into record of the inquest. In her statement, she refers to being injured in the leg:

I said I was a diehard anyway. Then the soldier next to me who did all the talking fired a shot from a revolver. I was then hit in the leg. I now make this declaration knowing that I am about to die from the wound consequent on the shot fired by the above referred to soldier.

The jury at the inquest decided that it had not heard sufficient evidence to satisfy itself whether the shooting was accidental or intentional.

Exactly one week later, Lt John Hunter went on trial at Tralee Courthouse for the killing of Hannah O’Connor. Depositions were read before Acting District Justice H.A. McCarthy. Evidence similar to that presented at the inquest was heard.

In a statement to the court, Lt Hunter said that after he realised what had happened, he did everything he could to find medical help. The local doctor in Glenbeigh was out on a call when he went to his home so he went to find a car which could transport Hannah O’Connor to Killorglin.

The judge decided however that he had no option but to send Hunter forward for trial.

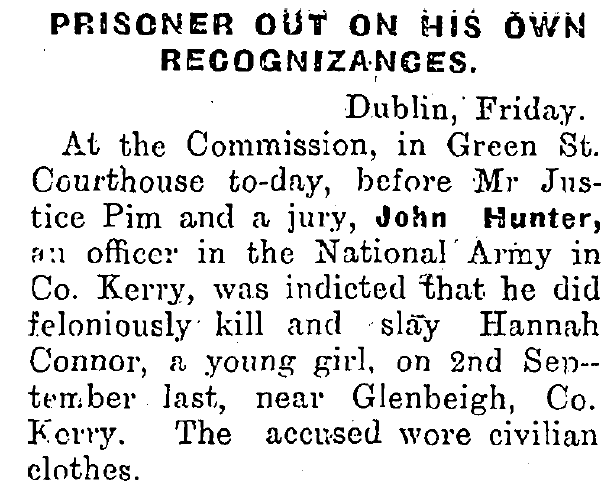

The trial took place at the Green Street Courthouse in Dublin in February 1924. Hunter was initially charged with murder but this charge was amended to one of manslaughter just before the trial commenced. Hunter, wearing civilian clothing, appeared before Mr Justice Pim and a jury of twelve men. The charge before the court was that Hunter ‘did feloniously kill and slay Hannah O’Connor, a young girl’ on 2 September 1923 near Glenbeigh, Co. Kerry. Hunter entered a guilty plea and expressed regret, insisting that he believed his weapon was not loaded.

For the prosecution, William Carrigan KC, described how Hannah and friends had walked to Glenbeigh where they enjoyed the dance for an hour and a half before they returned on foot towards Glencar. He described their encounter with the soldiers.

Carrigan admitted that O’Connor’s remarks about being a diehard ‘had no political significance’ but was rather ‘a cant in the neighbourhood’. The prosecution decried the ‘loose use of firearms’ as a matter ‘that those in authority should carefully see to’ and insisted that it was no excuse for Hunter to claim that he was unaware that the gun was loaded. Carrigan went on:

He [Hunter] should have taken care and should have known whether it was loaded or not. While it was not a case for a punitive sentence it was certainly a case for the consideration of a jury. This man was a lieutenant, and it was his duty to see that discipline should be maintained. For an officer to say that he was in the habit of carrying his revolver about unloaded, and because of that presented it at another, could not be tolerated.

In mitigation, the trial heard that Lt Hunter ‘did all in his power to assist the wounded girl and procured a car and brought her to a doctor.’ This contention was supported by Nancy Clifford. The head of the Civic Guards in Tralee, Supt. Hannigan, who interviewed Hunter after the shooting, told the court that Hunter seemed ‘very sorry for the whole occurrence.’

Finding Hunter guilty of manslaughter, the jury acknowledged that he had helped in getting the injured girl to a doctor and had accompanied her to Killorglin. Mr Justice Pim spared Hunter a custodial sentence: ‘You were guilty of a very serious offence, and it ought to be a warning to you and others not to handle firearms negligently.’ Hunter was bound to the peace for three years.

While the evidence and verdict amounted to an acceptance of Hunter’s account of events, and the incident had all the appearances of an unfortunate accident, the political undertones to the case were apparent, which was indicative of the tensions in the county in the months after the Civil War, and the rancour and bitterness which they had engendered.

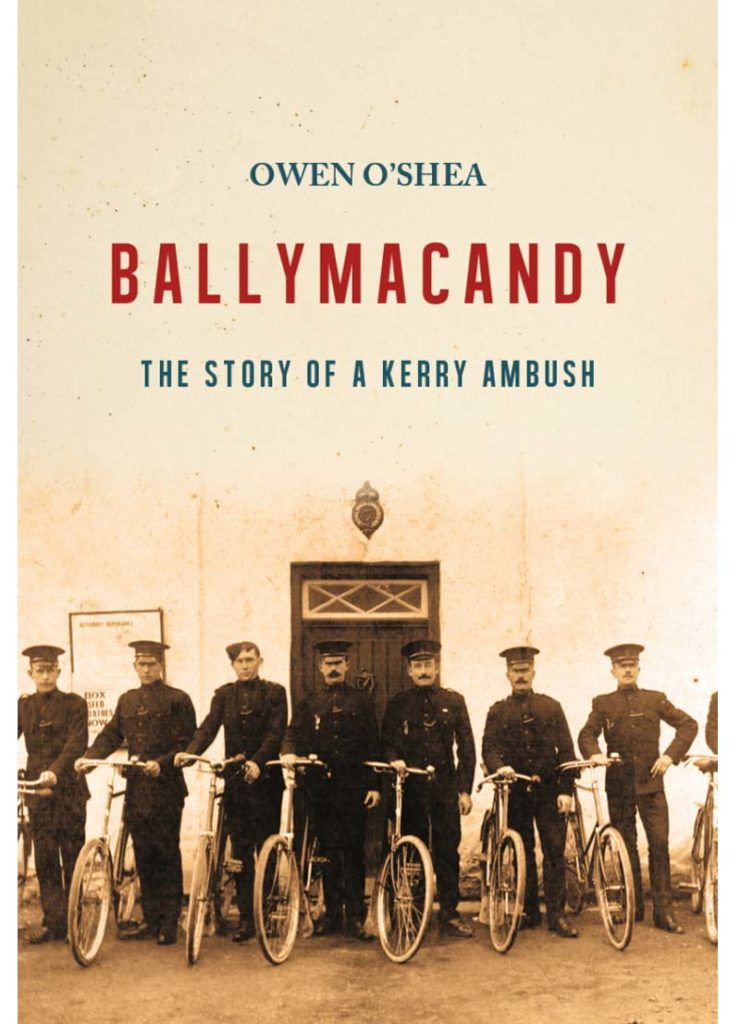

For more see: No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry – Irish Academic Press