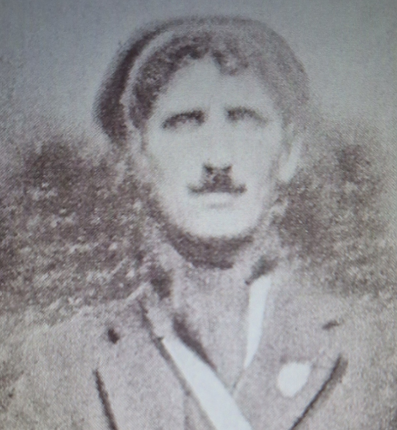

Daniel Sugrue was a man of divided loyalties. Like so many who felt compelled to join the Free State Army, whether through political conviction, military experience or financial necessity, Sugrue enlisted in October 1922.

A tailor from Dominick Street in Tralee, and later living at Brewery Lane in Killarney, he became the tailor for the Free State Army garrison in Killarney, which was based at the Great Southern Hotel.

Daniel’s wife, Mary, believed that her husband, in joining the army, was defending the recently established Cumann na nGaedheal administration against the anti-Treaty IRA: he had ‘the good of his country at heart’ and did ‘his utmost to prevent the overthrow of the present Government’.

But sources from the period suggest Sugrue held a more nuanced attitude towards his role as an army private and the spiral of violence which typified the Civil War in his native county. Sugrue was one of those in the new army, who, if not sympathetic to republicans and their cause, was at least willing to treat opponents and anti-Treaty prisoners with some dignity.

Though he had no known involvement in the IRA during the War of Independence, Sugrue may well have known some of those who were in jail in the cellars of the Great Southern Hotel, and he faced the dilemma of many of those in the army in 1922–23 about how to treat those in custody.

Sugrue’s actions in the spring of 1923 certainly belie the notion that all Free State soldiers in Kerry treated republican prisoners with universal cruelty and disdain. At a minimum, Sugrue treated prisoners in the Great Southern Hotel with a kindness they were denied by so many of his fellow soldiers. Conditions in the cells were grim: ‘the walls were moist and the blankets, the only thing in the cell, were soaking’.

In March 1923, his superiors discovered that Sugrue was smuggling in the occasional bottle of stout to the prisoners, as well as ‘what news he could’, but that he had warned them not to reveal his kindness for fear that he would be shot if his actions were revealed to his superiors.

The kindness of Sugrue was unusual and is starkly juxtaposed with accounts of the abuse and torture that took place in the prison cells – one detainee, Tadhg Coffey, was beaten unconscious with an iron poker – often signified by screams heard by local residents in the early months of 1923.

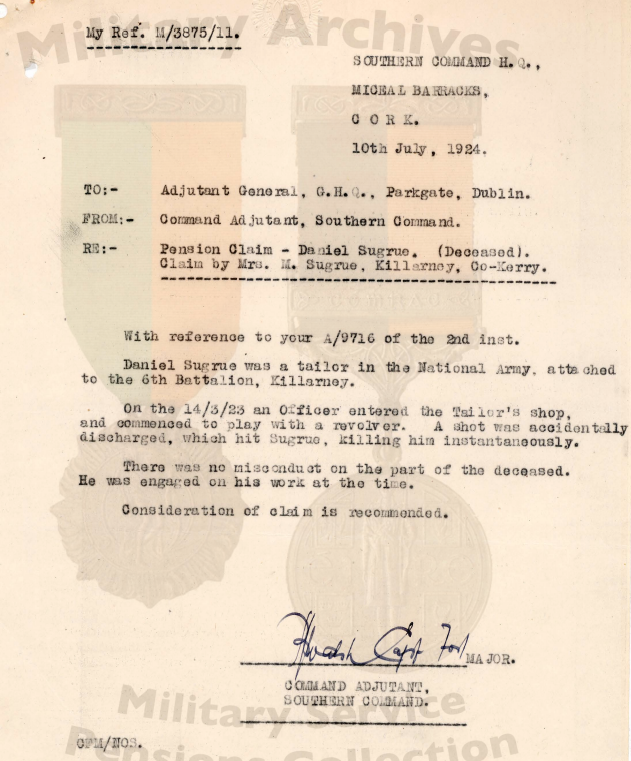

Official records state that on entering the tailor’s room in the barracks on the evening of 14 March, Private Sugrue began to ‘play with a revolver’, which was accidentally discharged, and he was killed instantly. He was attended to by Dr Murphy, the battalion’s medical officer, but the gunshot wound proved fatal.

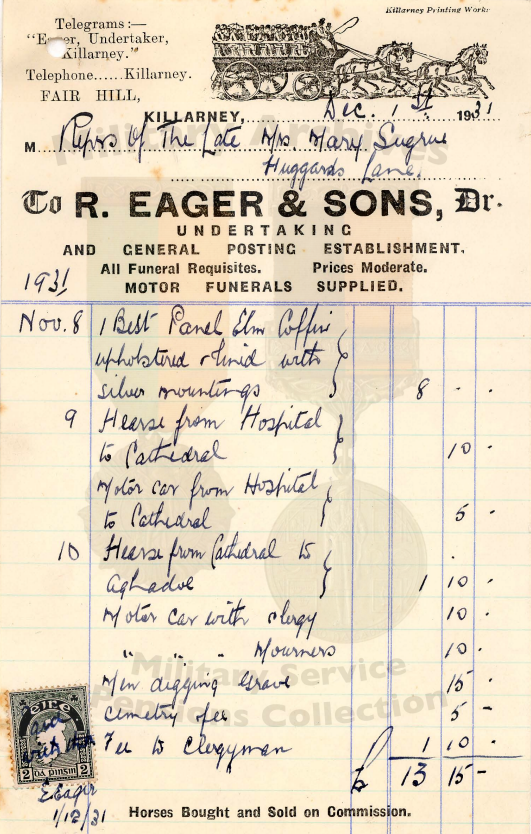

Sugrue’s widow, Mary – who was left impoverished and ‘exhausted’ after his death – claimed that no death certificate was issued and the Free State garrison ‘took all charge of all funeral arrangements’. In the absence of an inquest, it will never be possible to know precisely what happened to Daniel Sugrue, but other accounts suggest that there was no accident and that he met his death at the hands of his fellow soldiers.

A week after his colleagues murdered four IRA prisoners on the outskirts of Killarney, Sugrue appears to have been loose-lipped about what had occurred, and it was alleged that he may have been providing information to republicans. A report prepared for IRA headquarters offers a very different perspective about what happened in the Great Southern Hotel on the evening of 14 March:

A tailor named Sugrue from Killarney who was working in the Free State Barracks was murdered by an officer there on Wednesday evg [evening] 14th inst. He had been speaking to some of his friends in the town and was explaining how the Prisoners were murdered [at Countess Bridge] and how they were arrested – they were tortured by 14 of the Staters. When he returned to Barracks, he was shot dead. Of course, it appeared in the Press as the usual ‘accident!’

‘Murder of Republican Prisoners in Kerry’, UCDA, Papers of Moss Twomey, P69/26 (9); McMahon, ‘Civil War Violence in Kerry’, p. 60.

The account was supplemented by the testimonies of families, which were gathered by Dorothy Macardle for her 1924 book Tragedies of Kerry.

The death of Private Daniel Sugrue at the hands of his fellow soldiers represented a new and further descent in the downward spiral of indiscipline and violence within the ranks of the Kerry Command, but also exemplified the litany of cover-ups which came to characterise the policy and approach of the Command in the spring of 1923.

Extract from ‘No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry’ by Owen O’Shea: No Middle Path: The Civil War in Kerry – Irish Academic Press