On the 50th anniversary of the death of former Taoiseach and Fianna Fáil leader, Seán Lemass, here is an extract from the memoirs of Kerry South TD, John O’Leary (which I ghosted in 2015) which describes how a visit by Lemass to Killarney in the early 1960s led to the introduction of Ireland’s first major laws on planning permission.

From ‘On the Doorsteps: Memoirs of a long-serving TD’ by John O’Leary (Irish Political Memoirs, 2015)

New laws requiring people to obtain planning permission to build a house or any development in rural Ireland came about almost by accident. The introduction of a planning regime for non-urban areas was prompted by a visit the then Taoiseach, Seán Lemass, made to Killarney in the early 1960s. It is extraordinary to think that there was no legal requirement for planning permission in rural areas at the time. Cities and towns which had an urban district council, like Killarney, Tralee and Listowel, did have a planning regime in place but county councils had no planning departments at all; you could build a skyscraper on your own land in a rural area if you wanted to, and you could do so perfectly legally because there was no law, up until the mid-1960s that is.

I remember being told by Pat O’Halloran, who was county manager in the early 1960s, about Lemass visiting the Hotel Europe, a five-star hotel between Killarney and Fossa, beautifully located on the shore of the Lakes of Killarney. He was dining with the German owner, Hans Liebherr, whose family had built and opened the hotel. They also owned and operated a thriving container crane manufacturing plant on the outskirts of Killarney – a company that continues to prosper to this day. Lemass was sitting down between Liebherr and O’Halloran, looking out the window across the lake and towards Tomies mountain.

The Taoiseach was admiring the beauty of the place when he turned to Liebherr and said that it must have been very difficult to get planning permission for the hotel in such a beauty spot. Liebherr said that it hadn’t been a problem at all; in fact, he hadn’t needed to apply for planning permission in any shape or form because the hotel was outside the Killarney UDC area.

Liebherr told the Taoiseach that the county manager sitting beside him looked after all matters concerning planning outside of the urban districts. Lemass was shocked; apparently, he had no idea that there was no requirement to seek planning permission in rural Ireland.

Glancing across the lake and thinking about what he had been told, Lemass asked, ‘Does that mean that across there at the foot of that mountain, you could build half a dozen more hotels without any planning permission?’. ‘It does,’ was the county manager’s reply. Before parting company with his guests that evening, Lemass hinted that he would be having a serious chat about planning with his Minister for Local Government, Neil Blaney, on his return to Dublin.

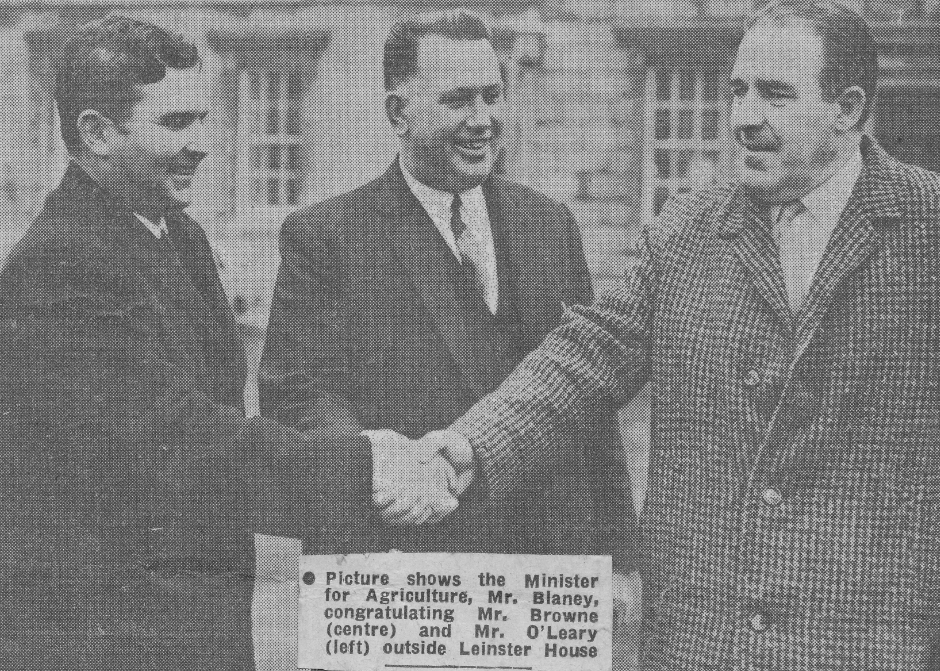

When Lemass got back to Leinster House, he sent for Blaney and questioned why there were no planning permission requirements in rural areas, referring to his experience in Killarney. Blaney later told me he tried to pacify Lemass, saying that while he accepted that something could be done in sensitive beauty spots like Killarney, there was no need for planning legislation nationwide. He argued that people had been building on their own land for years and there hadn’t been any major problems. Lemass wouldn’t hear of it, though; he insisted that a copy of the British Planning Act be found as quickly as possible and that it be used as a template for a new bill. Much of what was in the Westminster legislation was simply copied over into Irish law and the Planning Act (1963) came into effect on 1 October 1964. It remains the basis of the planning laws we have today.

In many ways, the Planning Act (1963) was introduced at the right time as it fitted naturally with Lemass’ programme of economic expansion and recovery. There was a noticeable shift towards building private houses and away from the reliance on the councils to build single rural dwellings. Despite the regulations and requirements in planning conditions, young people still preferred to be able to build on a site they were given by their parents rather than having to turn to the council to build a house for them. Those requirements haven’t changed much over the years; an applicant needed an engineer or architect to draw up plans to be submitted to the council for consideration. New restrictions, for example, meant that houses had to be a certain distance back from the public road as road improvements were beginning at that time.

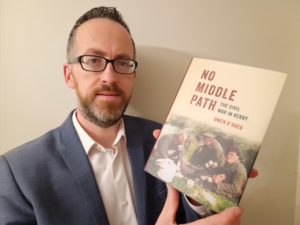

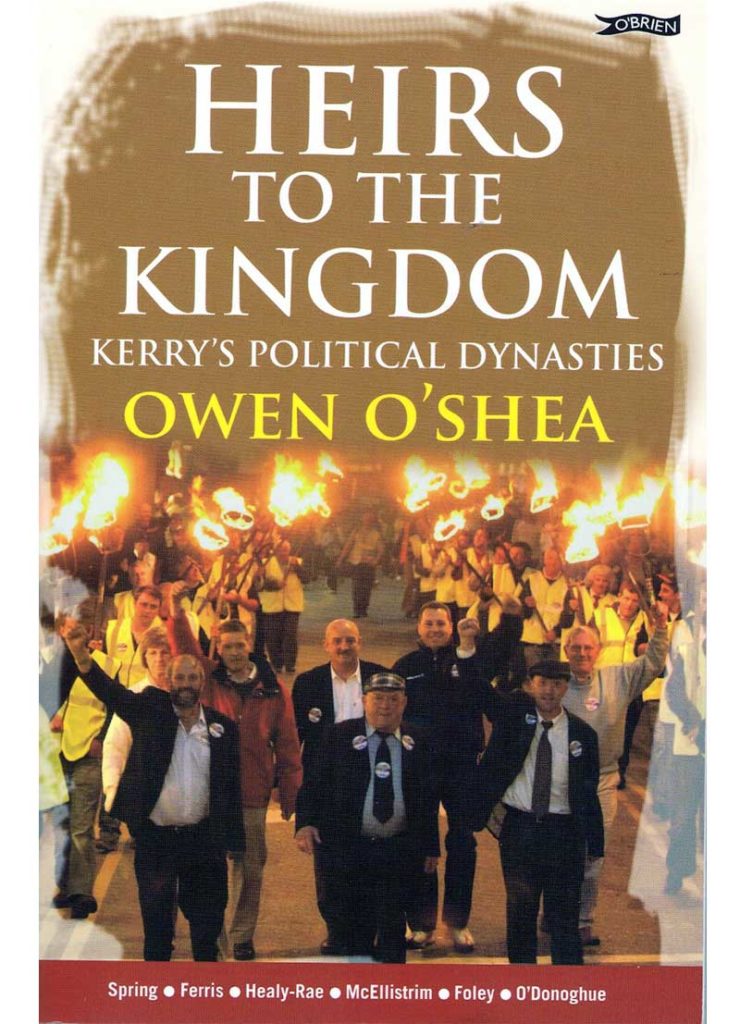

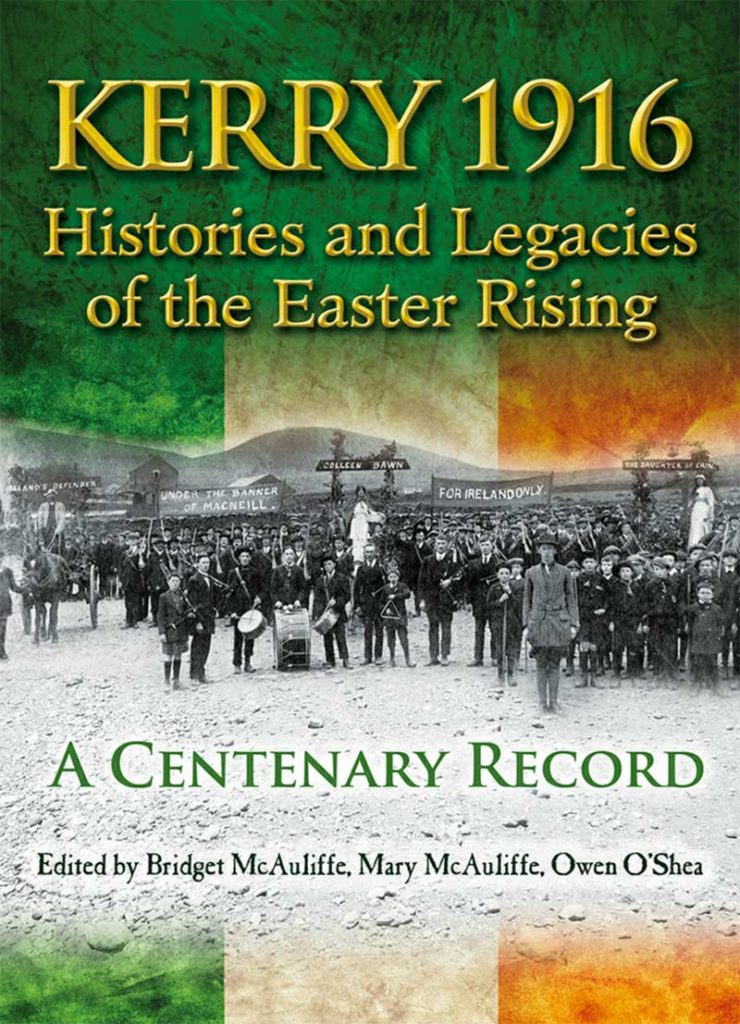

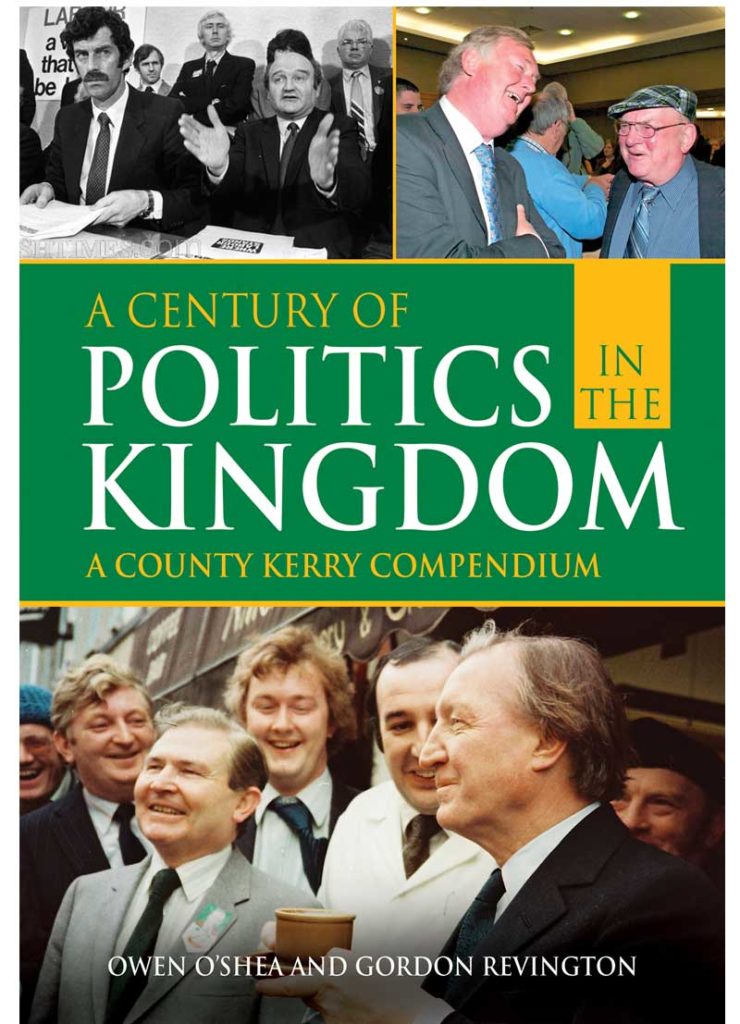

Books – Owen O’Shea (owenoshea.ie)

Book is available from Eason, Killarney