Learnings from researching the ambush at Ballymacandy

History isn’t really an interest of mine: it’s more like an obsession. It’s difficult to adequately articulate what makes one want to constantly find out more about the past but I’ve always been fascinated by what came before us and how it informs our lives, our attitudes and our society and politics today.

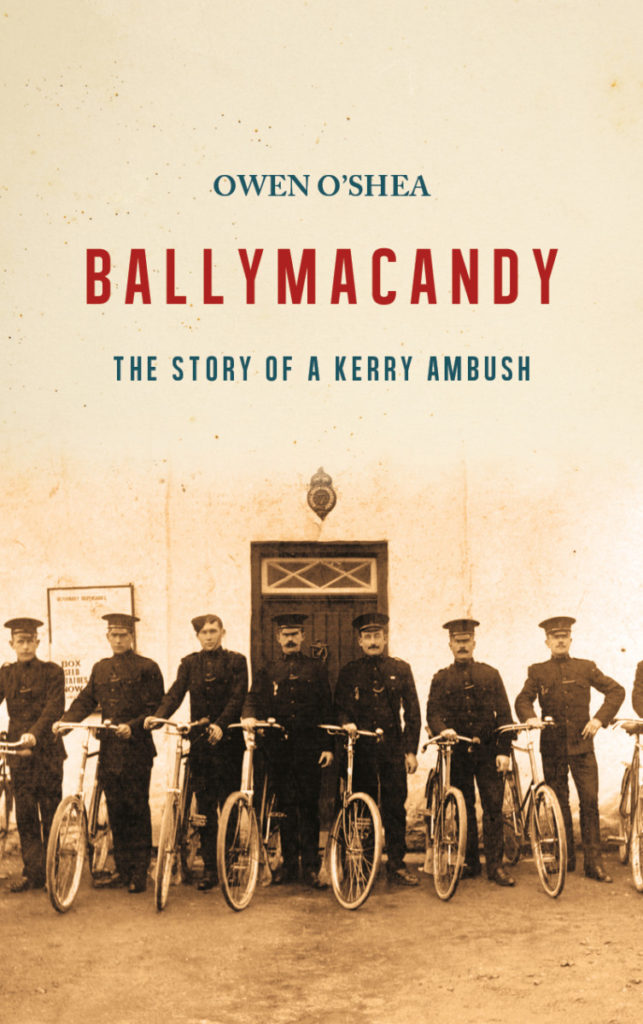

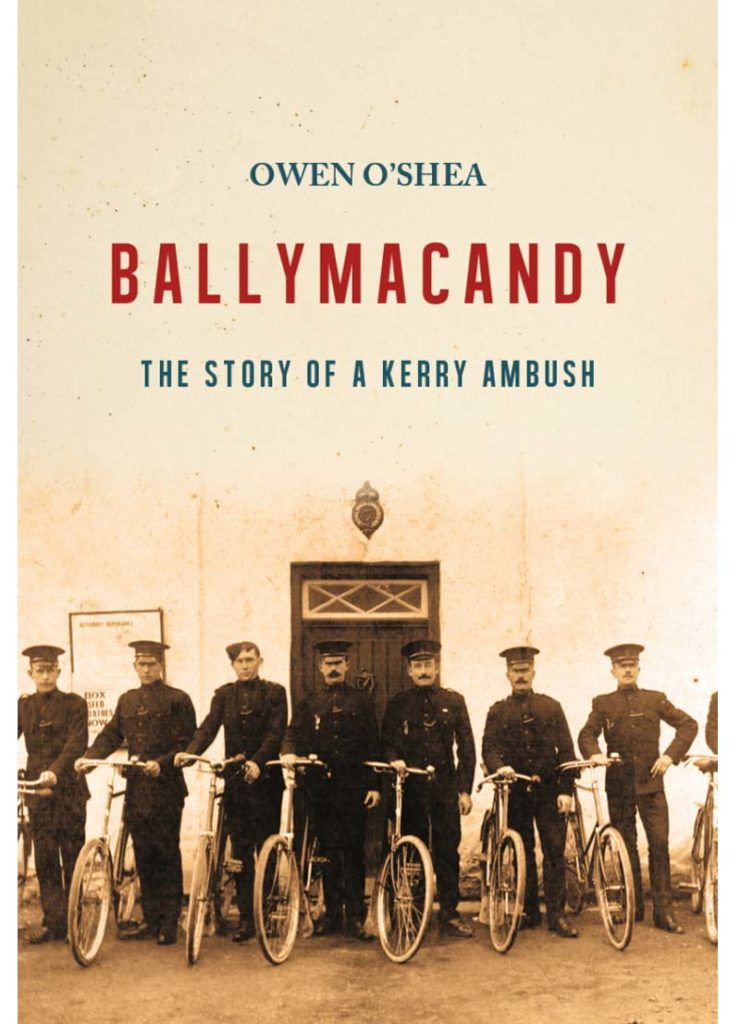

Few things give me more of a thrill than unearthing something new from the past, an obscure reference in an archive document, a clue in a letter from a century ago, a handwritten scribble on an official document, or an unpublished photograph of someone involved in shaping our history. At times, during the writing of my new book, ‘Ballymacandy: the Story of a Kerry Ambush,’ I felt like a forensic detective, piecing together and cross-checking different snippets of evidence to create as detailed a narrative as possible.

Oddly enough, the War of Independence and the Irish revolution was never an area which interested me more than any other. In fact my Masters Degree in UCD many years ago was on British history and the early life of King James II – although he did have an Irish connection! But the book I edited with Bridget McAuliffe and Mary McAuliffe on Kerry and the 1916 Rising a few years ago reignited my interest in the history of the Irish revolution.

As the centenary of the Ballymacandy ambush of 1 June 1921 approached, and as someone who grew up a stone’s throw from where the incident happened a century ago, I felt compelled to find out what happened, not just to satisfy my own curiosity but to use whatever research skills I have to share the story of what occurred with my neighbours and friends in my community and beyond.

This, after all, was the turbulent and tumultuous period which led to the foundation of our state, a period in which thousands of men and women died, in which communities were terrorised, in which so many people were injured and traumatised, in which there was political upheaval, an era which has left such a long and sometimes difficult legacy. But difficult history should never be ignored history or invisible history.

How can we not confront and interrogate the brutalities of this period, despite their grotesqueness and savagery? The story of Maggie Slattery of Milltown Cumann na mBan, dragged from her burning home by the Auxiliaries and hauled in front of the notorious Major Mackinnon who ripped apart the rosary beads she wore around her neck? Or the priest in my local church who ordered the Black and Tans to ‘get out of the House of the God? Or the killing of RIC sergeant James Collery, a man as Irish as the men who slayed him, leaving a widow and nine children, one of whom died a few months later? Or the local women brutally targeted by the IRA for the crime of ‘company keeping’ with the police? A sad and cruel history but our history nonetheless.

A book like ‘Ballymacandy’ doesn’t get written without the input of people who knew those involved in the incident – the descendants of the protagonists on both sides of the conflict. Pride and an overwhelming willingness to engage with someone interested in telling the story of their loved ones were the universal reactions. I am deeply grateful to people who knew a little but have now ensured that we know a lot.

One memory that will stay with me is the constant refrain, ‘They didn’t really talk about it,’ a comment from most of the relatives I approached for information. There may have been an awareness that granddad or grandma was ‘involved’ in some way. There might have been sketchy details but no specifics. Some have told me they had no idea their ancestors were in Cumann na mBan or the IRA or Fianna Éireann.

It is easy to understand why ‘they didn’t really talk about it.’ There was violence, murder, bloodshed, terror, hardship and poverty. In the interests of peace and progress, there was a conscious effort by many to confine the past to the past: the Kerry Fianna Fáil TD and War of Independence veteran, Tom McEllistrim claimed the entire period was ‘best left to history.’

Thankfully, a century on, though still relatively fresh in the communal memory, we can now discuss more freely, and with a wider range of perspectives, the War of Independence with the benefit of so many first-hand accounts published in recent years by the Military Archives. Those accounts, despite some inadequacies and imperfections, offer us new hugely valuable insights and details which were previously unknown.

Throughout my research I thought much about the ordinary civilians caught up in the conflict. How must my grandfather, then a 14-year-old boy living on Main Street in Milltown, have reacted as he saw Black and Tans go on the rampage in his village in November 1920 or when he saw dead constables being taken the church after the Ballymacandy ambush on a hot summer’s evening in 1921? As I discovered during my research, his father, my great-grandfather, had been among those who nominated Austin Stack at the pivotal 1918 general election.

I knew before writing Ballymacandy that history is complicated, it’s often controversial, it’s full of nuances, twists and turns, disagreements, different interpretations, multifaceted interconnections and a complex web of overlapping relationships and inter-personal forces simmering beneath the surfae. Nothing is black and white. And my research on this traumatic episode in the life of my community convinced me of all those things.

But it also convinced me of something that never changes – history is enthralling and without knowing and appreciating our history, we are all the poorer. As the Jamaican activist, Marcus Garvey proclaimed: ‘A people without the knowledge of their past history, origin and culture is like a tree without roots.’

‘Ballymacandy: the Story of a Kerry Ambush’ is published by Merrion Press and now available to order/buy on: Ballymacandy: The Story of a Kerry Ambush – Owen O’Shea (owenoshea.ie)